Christ Church Cathedral | Map

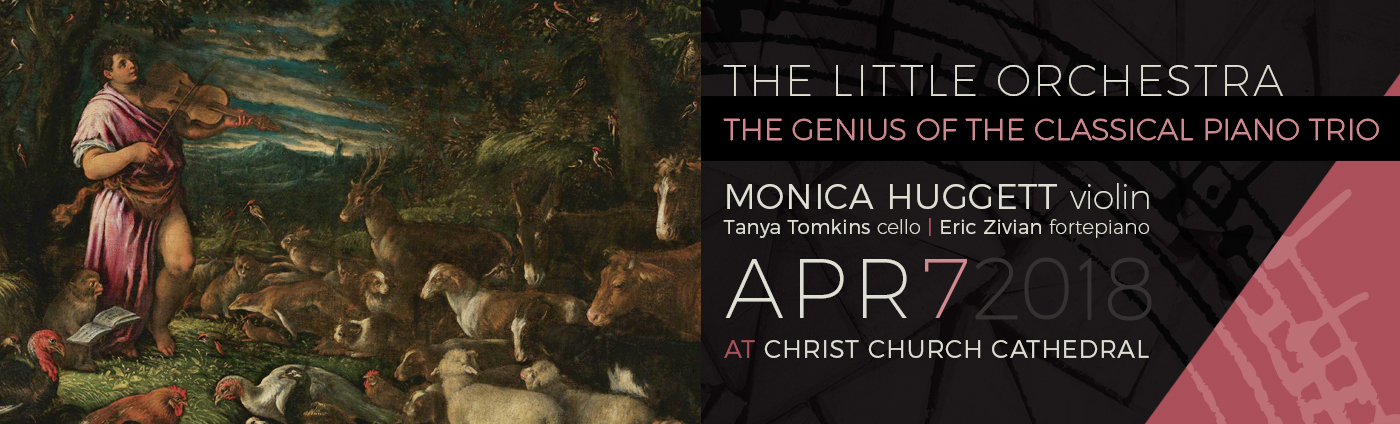

Monica Huggett, violin; Tanya Tomkins, cello; Eric Zivian, fortepiano

The “Little Orchestra” is a snapshot of an early moment in the history of the evolution of the fortepiano on its way to becoming the modern grand piano. Played on original instruments, the potential balance issues inherent with the use of modern instruments in this highly refined repertoire are avoided, and the violin and cello play more equal roles, allowing the charm, wit and subtlety of these works to occur naturally. Music by Mozart, Haydn and Beethoven.

Supported by Mary Christopher

Click here for information about parking around / transiting to Christ Church Cathedral

Programme

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791)

Piano Trio in C Major, KV 548

- Allegro

- Andante cantabile

- Allegro

Franz Josef Haydn (1732-1809)

Piano Trio in G Major, “Gypsy”, Hob. XV:25

- Andante

- Poco Adagio

- Finale. Rondo all’Ongarese: Presto

INTERVAL

Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827)

Sonata No. 4 for Violin and Piano in A Minor, Op. 23

- Presto

- Andante scherzoso, più Allegretto

- Allegro molto

Johann Nepomuk Hummel (1778-1837)

Piano Trio in F major, Op. 22

- Allegro moderato

- Andante con variazioni

- Rondo alla Turca: Vivace

Programme Notes

Every job has its perks and drawbacks. For instance, Joseph Haydn was employed by the Esterházy family, the wealthiest family in the Hungarian nobility, for most of his career. This plum job ensured a cushion of financial stability and a full-time orchestra at his service. The catch, however, was that he was obliged to spend his time in the small city of Eisenstadt, near the Austrian-Hungarian border, as well as at the even more remote summer residence of the family at Esterháza, deep in the Hungarian countryside. In 1804, Johann Nepomuk Hummel inherited the position, bound to grapple with the same issues. Hummel, an insatiable man-of-the-world, fared somewhat worse in the position than Haydn. He was dismissed in 1808 for being too engrossed in the musical scene in Vienna to pay attention to his duties at court.

Despite the isolation that plagued this position, it also provided access to Hungarian musical traditions, which held great fascination to audiences in Austria and the rest of Europe. Aware of this, Haydn and Hummel both experimented with Hungarian idioms in some of their compositions, several of which are on display here. However, the nature of their experience with Hungarian folk music deserves scrutiny. Life at court was largely segregated from Hungarian peasant life. Accordingly, most of Haydn’s and Hummel’s contact with Hungarian folk traditions was through the military, and it is this military music that finds its way into their compositions.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Piano Trio in C Major, KV. 548

Before we turn to Hungary, however, our evening begins with Mozart’s late-period Piano Trio in C Major, KV. 548. The work was written in 1788, during an extraordinarily fruitful summer—even by Mozart’s standards. During the season, he composed his iconic, final trilogy of Symphonies Nos. 39, 40, and 41 (the “Jupiter”), as well as another first-rate piano trio, the E major, KV. 542, and a handful of other works. The C major trio, clearly ideological kin to these other works, can be praised for its elegance and restraint.

The first movement opens with an assertive principal melody in unison octaves. However, any sure-footedness is undercut by an exceptional development section, which dwells in unsteady minor-key territory and fixates on a chromatic sigh motive, until finding its way back to the home key. The second movement, a lyrical Andante cantabile, points forward in time to the nineteenth century, and a jaunty rondo finale, one which clearly shares genetic material with Mozart’s piano concerti, concludes the piece with a smile.

Franz Josef Haydn, Trio in G Major, “Gypsy”, Hob. XV:25

Unlike the string quartet, which for Haydn was a place for serious intellectual exchange and conspicuous cleverness, the piano trio was reserved for gracious, sociable music. Accordingly, his Trio in G Major, No. 25 abounds with welcoming textures and good humor. The piece was written in 1795, just after Haydn had returned to Vienna from a successful visit to London. Haydn published it as part of a set of three trios which were dedicated to Rebecca Schroeter, a wealthy widow who was his music copyist in London, and with whom he had a romantic attachment. Yes, Haydn was married at the time, but his union with Maria Anna Theresia was an unhappy one, and infidelities abounded on both sides.

Instead of the expected sonata-form Allegro, Haydn welcomes his audience with an Andante, which alternates two themes rather than substantively developing them. The lilting second movement is derived from the Adagio of his Symphony No. 102, written in the same year. But the true gem of the trio is the infectious finale, a Rondo all’Ongarese. Here, Haydn lets loose with a bravura display of verbunkos-style flourishes, such as um-pa bass patterns, abrupt turns to chromatic-inflected strains of darkness, and Hungarian fiddle techniques such as left hand pizzicato.

Beethoven, Sonata No. 4 in A Minor, Op. 23

Nine out of Beethoven’s ten violin sonatas were completed in a span of five years, relatively early in his life as a composer—between 1798 and 1803. The first three, Op. 12, are salon pieces at heart. They are full of well-balanced phrasing and tuneful pleasures, albeit interrupted by Beethoven’s typical penchant for surprise. In his fourth sonata, however, Beethoven revealed his aptitude for development, a trait that would propel his music for the remainder of his career. This sonata and the next—the celebrated Op. 24, known as the “Spring” Sonata—were intended to be a set, and were originally published as such in 1801. However, they could hardly be more different. Whereas the “Spring” Sonata is effusive and relaxed, this one presents remarkable terseness, which saturates its melodic material and the treatment of its formal structures. The work also captures the intensity and fire of the young composer.

The first movement is in a restive 6/8, an unusual choice for the opening of a sonata. A compelling and lengthy development section, as well as a rhetorically powerful coda, carry the interest here. In the second movement, the motoric energy of the first seems to have died away in favor of something quirkier and more enigmatic. This movement is cast as a duple-meter Andante with pronounced silly, scherzo-like attributes. A series of cleanly articulated phrases take turns introducing a colorful cast of characters, followed by a brief developmental interlude, and we return to the beginning, with piano and violin exchanging roles and ornamenting whimsically. The finale reveals flashes of virtuosity and playful wit among more straight-faced statements of operatic drama. Here, Beethoven seems to eschew any strong sense of large-scale structure, only adding to the unpredictability that permeates the work. It ends, like the other two movements, with a whisper.

Hummel, Piano Trio in F major, Op. 22

Hummel’s splendid Piano Trio in F Major, Op. 22 was written in 1799, before he took his position in the Esterházy household. However, it was not published until 1807—around the same time as his Balli Ongarese.

The first movement’s easy lyricism and energetic outbursts align the work with Mozart’s compositions in the same genre, and it feels fitting to compare this work with the Mozart trio that opened the program, written eleven years prior. The lilting 6/8 meter, reliance on sweet thirds in the melody, and F Major tonality show Hummel’s interest in the pastoral. The recapitulation in this first movement is unusual—instead of fully and triumphantly returning us to the opening strains, Hummel softens any hard-edged transition, giving us a paraphrase of the second theme, as well as some transitional material. The climactic moment comes in the form of a surprise, a fugal treatment of this second theme that precipitates the movement’s close.

In the second movement, all three instruments are given plenty to do, trading virtuoso flourishes and counter-melodies that decorate a disarmingly simple theme in a set of variations. The finale is a bracing Rondo alla Turca, reminiscent of the finale of Mozart’s Piano Sonata No. 11 in A Major (1783). Both works exploit an eighteenth-century fascination with the Ottoman Empire. The Ottoman Turks were considered a substantial threat to Austrian culture at the time, as historical memory had not yet forgotten the dramatic two-month siege of Vienna in 1683 by Ottoman forces. Here, Hummel writes brilliantly for all three instruments, but none more so than the piano, of which he was an undisputed virtuoso. Grace notes add exotic flair and charm, while propulsive runs create a race to the exuberant finish.

— Sophie Benn, 2018

Monica Huggett, violin

From age seventeen, beginning as a freelance violinist in London, Monica Hugget has earned her living solely as a violinist and artistic director and, in 2008, was appointed inaugural artistic director of The Juilliard School’s Historical Performance Program, where she continues as artistic advisor. Monica’s expertise in the musical and social history of the Baroque era is unparalleled among performing musicians today. This huge body of knowledge and understanding, coupled with her unforced and expressive musicality, has made her an invaluable resource to students of baroque violin and period performance practice through the 19th century.

Over the last 40 years, Monica co-founded, with Ton Koopman, the Amsterdam Baroque Orchestra; founded her own London-based ensemble, Sonnerie; worked with Christopher Hogwood at the Academy of Ancient Music and Trevor Pinnock with the English Concert; toured the United States in concert with James Galway; co-founded, in 2004, the Montana Baroque Festival; and has served as artistic director of Portland Baroque Orchestra since 1994, where she made her first appearance in 1992 playing Vivaldi’s Four Seasons. From 2006 to 2017, she was also the artistic director for Irish Baroque Orchestra, where she recorded Flights of Fantasy, named by Alex Ross in the New Yorker as Classical Recording of the Year for 2010.

Monica’s recordings, numbering well over 100, have won numerous prizes and acclaim throughout her career. In addition to her baroque violin recordings, she recorded “Angie” with The Rolling Stones in 1972. Monica lives in Portland, where she enjoys cycling and gardening (somewhat compulsively).

Tanya Tomkins, cello

Artistic Director and co-founder of the Valley of the Moon Music Festival, cellist Tanya Tomkins is equally at home on Baroque and modern instruments. She has performed on many chamber music series to critical acclaim, including the Frick Collection, “Great Performances” at Lincoln Center, the 92nd Street Y, San Francisco Performances, and the Concertgebouw Kleine Zaal.

She is renowned in particular for her interpretation of the Bach Cello Suites, having recorded them for the Avie label and performed them many times at venues such as New York’s Le Poisson Rouge, Seattle Early Music Guild, Vancouver Early Music Society, and The Library of Congress.

Tanya is one of the principal cellists in San Francisco’s Philharmonia Baroque Orchestra and Portland Baroque Orchestra. She is also a member of several groups including Voices of Music and the Benvenue Fortepiano Trio (with Monica Huggett and Eric Zivian). On modern cello, she is a long-time participant at the Moab Music Festival in Utah, Music in the Vineyards in Napa, and a member of the Left Coast Chamber Ensemble. As an educator, Tanya has given master classes at Yale, Juilliard, and the San Francisco Conservatory of Music, and is devoted to mentoring the next generation of chamber musicians through the Apprenticeship Program at the Valley of the Moon Music Festival.

Eric Zivian, fortepiano

Eric Zivian is a fortepianist, modern pianist and composer. He has performed with the Philharmonia Baroque Orchestra, the Portland Baroque Orchestra, the Santa Rosa Symphony and the Toronto Symphony, among others, and given solo recitals in Toronto, New York, Philadelphia, and the San Francisco Bay Area.

Eric Zivian has performed extensively on fortepiano since 2000 and is a member of the Zivian-Tomkins Duo and the Benvenue Fortepiano Trio, performing at Chamber Music San Francisco, the Da Camera series in Los Angeles, Boston Early Music, the Seattle Early Music Guild and Caramoor. On modern piano, he is a member of the Left Coast Chamber Ensemble and has performed with the Empyrean Ensemble, Earplay, and the San Francisco Contemporary Music Players. He is a founder and Music Director of the Valley of the Moon Music Festival, a new festival in Sonoma specializing in Classical and Romantic music on period instruments.

Eric’s compositions have been performed widely in the United States and in Tokyo, Japan. He was awarded an ASCAP Jacob Druckman Memorial Commission to compose an orchestral work, Three Character Pieces, which was premiered by the Seattle Symphony in March 1998. Eric studied piano with Gary Graffman and Peter Serkin and composition with Ned Rorem, Jacob Druckman, and Martin Bresnick. He attended the Tanglewood Music Center both as a performer and as a composer.