Christ Church Cathedral | Map

Marc Destrubé, baroque violin; Jacques Ogg, harpsichord; Telemann & C.P.E. Bach Chamber Works feat. Destrubé, Ter Linden, Ogg, Hazelzet, cello; Wilbert Hazelzet, baroque flute

Marc Destrubé and the three Dutch masters of the period instrument revival who will join him for this recital of chamber music by Telemann and C.P.E. Bach have been at the forefront of the international early music movement for over 30 years. All former instructors of our long-running Summer Baroque Instrumental Course at UBC, these four great artists have played pivotal roles in inspiring and teaching the next generation of Early Music artists. They have also individually enjoyed long and illustrious careers as soloists, chamber musicians and musical leaders all over the world – we could not imagine programming EMV’s 50th anniversary without them. This programme will feature a selection of highly expressive chamber music from the late 18th century repertoire known as the Style Galant.

To view/download the programme, click here.

This concert is generously supported by José Verstappen

Programme

Carl Phillip Emmanuel Bach (1714 – 1788)

Sonata in d minor for flute, violin and basso continuo, Wq.145 (Berlin 1747)

– Allegretto

– Largo

– Allegro

Georg Philip Telemann (1681 – 1767)

Sonata in D Major for cello and basso continuo

(“Der getreue Musikmeister” TWV 41:D6, Hamburg 1728/29)

– Lento

– Allegro

– Largo

– Allegro

Jean-Philippe Rameau (1683 – 1764)

Concert V in d minor for harpsichord, flute and violin

(“Pieces de Clavecin en Concerts,” Paris 1741)

– La Forqueray, Fugue

– La Cupis

– La Marais

INTERMISSION

C.P.E. Bach

Sonata in D Major for harpsichord and violin, WQ.71 (Potsdam 1747)

– Poco adagio

– Allegro

– Adagio

– Menuet I & II

Jean Marie Leclair (1697 – 1764)

Sonata in e minor for flute and basso continuo, Op.9 No. 2 (Paris, 1743)

– Dolce: Andante

– Allemanda: Allegro ma non tropo

– Sarabanda: Adagio

– Minuetto: Allegro non tropo

Telemann

Concerto Primo in G major for flute, violin, violoncello and basso continuo TWV 43 G1

(“Six Quatuors”, Paris 1730)

– Grave

– Allegro

– Largo – Presto – Largo

– Allegro

Programme Notes

In the middle of the Eighteenth Century, European courtiers were expected to be galant. This term first appeared in writings of seventeenth-century authors such as le Chavalier de Méré, who wrote a series of Conversations describing the ideal way to conduct oneself in courts of the nobility. To be galant was to be “sparkling”, “cheerful”, and to know how to insinuate oneself into a conversation. A successful galant courtier would be knowledgeable but not overly learned—in a modern sense, a Renaissance Man rather than a scholar. Some opponents of this aesthetic decried a galant homme as overly effeminate, and yet by the early Eighteenth Century, such protests did not disappear but certainly diminished. In music, embracing the galant aesthetic resulted in certain changes from the more dramatic, contrast-riddled world of the Baroque. “Learned” techniques such as fugues and dense counterpoint gave way to lighter textures where a charming melody reigned supreme over the highly subordinated lower parts. Unexpected changes in harmony or rhythm became not elements to dramatically shock but rather to delightfully surprise. Whereas conversational imitation of musical ideas between parts could sometimes (but not always) be heard as argumentative in earlier styles, imitation almost always sounds flattering and agreeable in the context of the style galant. Not all composers, however, unilaterally adopted this change of ethos in their music as it became fashionable, and older techniques stood alongside the more modern, as evidenced in this program.

C.P.E. Bach’s Sonata in d minor, Wq. 145 presents us with some hallmarks of the style galant. Imitation between the flute and violin suggest an amorous dialogue, as one part does not counter the other with an immediate contrasting idea but rather frequent confirmations of what came before. Bach delivers surprises such as chromaticism and appoggiaturas (graceful dissonances) in a suave manner so as to delight rather than jar the listener. The bass, as typical in the style galant, seldom engages in the conversation but rather provides an unrelenting foundation, mostly of steady rhythm where the harmony changes relatively slowly and in even increments, giving a sense of nonchalance even at a quick tempo, such as in the third movement.

C.P.E. Bach, incidentally, took over his godfather Georg Philip Telemann’s job in Hamburg when the latter died. Hamburg, as a highly cosmopolitan city, exposed the older Telemann to recent developments in musical style as they became fashionable. Even though it was composed in 1728 at the emergence of galant music, Telemann already embraced that aesthetic in his Sonata in D major for cello and continuo TWV 41:D6. The work was published in his Getreue Musikmeister, a publication aimed at delineating all of the current styles in the major Western European nations for the edification of musicians and connoisseurs. One of the most salient galant features appears in the first movement—the surprise appearance of triplets in a work where the beat is primarily duple. Such a rhythmic device was novel, considering that movements generally maintained a highly consistent rhythmic character in the music of the preceding decades. The triplets have the effect of a flirtatious laugh, very in keeping with the galant aesthetic.

If Telemann’s 1728 piece looked forward, Rameau’s 1741 publication of his Pièces de Clavecin en Concerts maintained some rather conservative compositional techniques. The fifth Concert in d minor contains three character pieces named after famous musicians of the previous generation: the viola da gamba virtuosi Forqueray and Marais, and the violinist and dance master Cupis. Rameau himself commented on the contrapuntal complexity of the music—a learned, not so galant aspect—when he says in the preface “I thought it necessary to publish a score, because it is necessary that the instruments not get confused with each other.” In fact, it was more common (and cheaper) simply to print only partbooks for the individual players, but for practical reasons, we see Rameau acknowledging the possibility for players to get lost in the musical tapestry he weaves.

The remaining pieces also stand on the more conservative side. Bach’s Sonata for harpsichord and violin strongly resembles those in the vein of his father Johann Sebastian, which is unsurprising given that it was written in 1731 and later revised. At that early date, Bach, in more remote Leipzig than Telemann’s Hamburg, would have had less access to the newest music trends. Italian-trained Jean-Marie Leclair’s Sonata in e minor is equally conservative and completely in the vein of the Italian baroque chamber sonata form popularized by Arcangelo Corelli. Telemann’s so-called Paris Quartets, including the concerto on this program, use a very baroque equal treatment of voices, as they were written for some of Paris’s most gifted musicians of the day, who were all equally talented. Telemann had a great gift for writing in multiple styles appropriate to the situation at hand, as evidenced on this program.

— Justin Henderlight

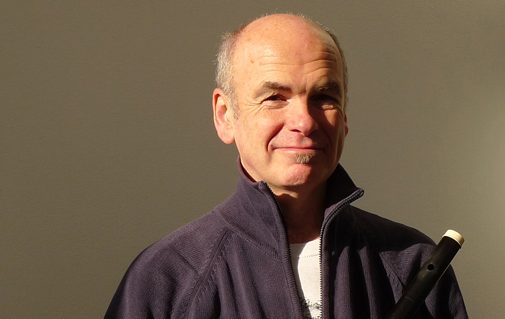

Marc Destrubé, baroque violin

Canadian violinist Marc Destrubé is equally at home as a soloist, chamber musician, concertmaster or director/conductor of orchestras and divides his time between performances of standard repertoire on modern instruments and performing baroque and classical music on period instruments.

As a concertmaster, he has played under Sir Simon Rattle, Kent Nagano, Helmuth Rilling, Christopher Hogwood, Philippe Herreweghe, Gustav Leonhardt and Frans Brüggen. He is co-concertmaster of the Orchestra of the 18th Century with which he has toured the major concert halls and festivals of the world. He was concertmaster of the CBC Radio Orchestra from 1996 to 2002, concertmaster of the Oregon Bach Festival Orchestra, and founding director of the Pacific Baroque Orchestra.

He is first violinist with the Axelrod String Quartet, quartet-in-residence at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington D.C., where the quartet plays on the museum’s exceptional collection of Stradivari and Amati instruments. He has also performed and recorded with L’Archibudelli and is a member of the Turning Point and la Modestine ensembles and Microcosmos string quartet in Vancouver.

He has appeared as soloist and guest director with symphony orchestras in Victoria, Windsor, Edmonton and Halifax as well as with the Australian Brandenburg Orchestra, Portland Baroque Orchestra and Lyra Baroque Orchestra. A founding member of Tafelmusik Baroque Orchestra, he has appeared with many of the leading period-instrument orchestras in North America and Europe including as guest concertmaster of the Academy of Ancient Music and of the Hanover Band.

Marc has recorded for Sony, EMI, Teldec, Channel Classics, Hänssler, Globe and CBC Records.

Jacques Ogg, harpsichord

Jacques Ogg is a performer and recording artist on both harpsichord and fortepiano, as well as a conductor. He teaches at the Royal Conservatory in The Hague. He was born in Maastricht (The Netherlands) and studied harpsichord in the city of his birth with Anneke Uittenbosch. In 1970 he went to study with Gustav Leonhardt at the Amsterdam Conservatory, from which he graduated in 1974. He currently serves as Professor of Harpsichord at the Royal Conservatoire in The Hague, where he teaches primarily harpsichord.

Jacques Ogg’s current activities include solo recitals on harpsichord or on fortepiano, concerts with flautist Wilbert Hazelzet. He has been a member of the Orchestra of the 18th Century and has performed regularly with Concerto Palatino. He is frequently invited to conduct masterclasses and summer courses, among others in Juiz de Fora (Brazil) and Buenos Aires, in Mateus (Portugal), Salamanca (Spain) as well as in Cracow (Poland), Prague and Budapest. He was invited as a juror in competitions such as “Bach Wettbewerb” (Leipzig) and “Prague Spring”. Jacques Ogg is artistic director of the Lyra Baroque Orchestra in Minneapolis/Saint Paul.

Telemann & C.P.E. Bach Chamber Works feat. Destrubé, Ter Linden, Ogg, Hazelzet, cello

Wilbert Hazelzet, baroque flute

Wilbert Hazelzet started his career in 1972 in Musica Antiqua Amsterdam (Marie Leonhardt); he has been principal flautist of The Amsterdam Baroque Orchestra(TonKoopman) from 1978. He was member of Musica Antique Köln until 1985; with Ensemble Sonnerie London and Cantus Coelln he performed until 1995.

Apart from his recitals with Jacques Ogg and lutenist Joachim Held, Hazelzet is a frequent guest in The Lyra Baroque Orchestra Minneapolis, Camerata Kilkenny, Passamezzo Antiguo Bilbao and Musica Amphion Netherlands.

Erato France, Die Deutsche Grammophon Gesellschaft – Archiv Hamburg, edel-Classics Berlin, Harmonia Mundi Germany, Philips, Harlekijn and Globe Holland, Virgin-EMI London and Glossa Music Spain published Hazelzet’s recordings.

Hazelzet teaches at the Conservatories of The Hague and Utrecht; his masterclasses take place at the universities of Salamanca, Granada, Seville, Vancouver, London and Minneapolis.