The Chan Centre for the Performing Arts

Please note: Tickets will also be available to purchase at the door on concert day starting 02:00 p.m.

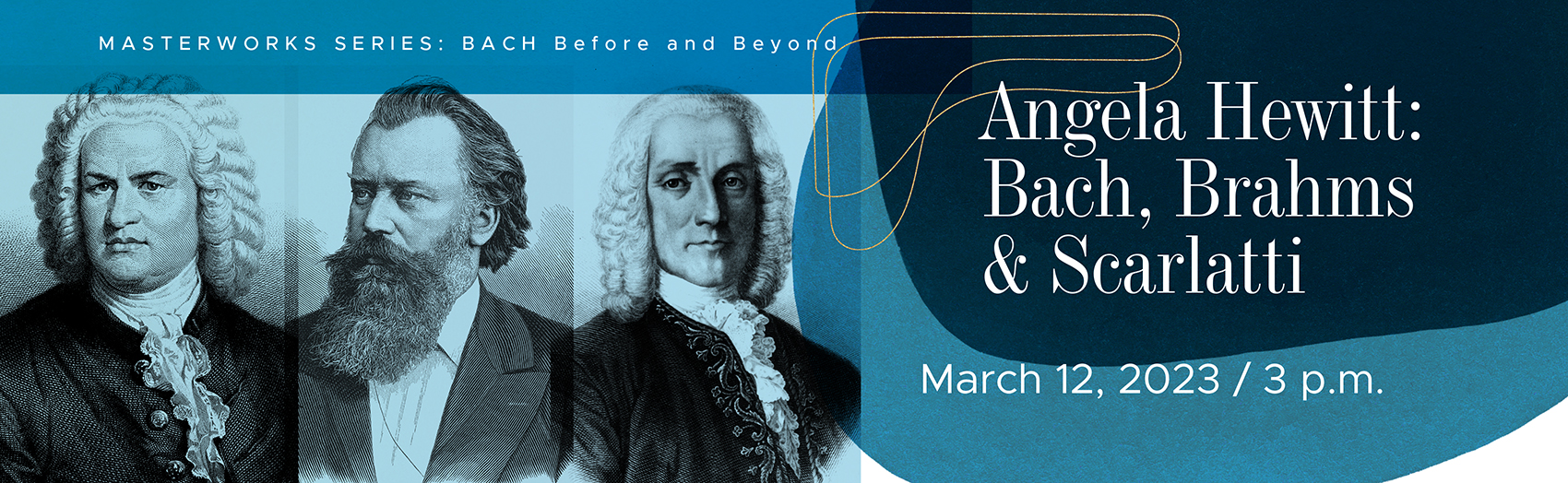

Angela Hewitt returns to EMV with Scarlatti, Bach and Brahms. Ms. Hewitt has become one of Bach’s foremost interpreters of our time. In her own words “Bach’s music cries out for a keyboard instrument that imitates the human voice. These days, you don’t hear so much discussion (about whether to play Bach on the piano), and there are as many ways of Bach on the piano as there are pianists. What I try to do is not think of it so much as keyboard music but as music that imitates the voice or the orchestra. It’s not piano music in the way Brahms or Chopin is piano music.”

Ms. Hewitt will be playing Bach’s English Suite No. 6 in D minor, preceded by a selection of Scarlatti sonatas and followed by Brahms’ Sonata in F minor Op.5. After her recent performance at Wigmore Hall, Martin Kettle from The Guardian commented “The beautifully sustained andante, which seems to slip in and out of the harmonic world of Beethoven’s Pathétique sonata, was the highlight of the evening. Truly a woman who can play Brahms, too.”

This concert is generously supported by Eric Wyness and Mark De Silva.

PROGRAMME

Domenico Scarlatti (1685-1757)

Kk 1 in D minor

Kk 446 in F major

Kk 531 in E major

Kk 420 in C major

Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750)

English Suite No. 6 in D minor

Interval

Johannes Brahms (1833–1897)

Sonata in F minor Op. 5

PROGRAMME NOTES

“When I am able to practice regularly, then I really feel completely in my element; it is as though an entirely different mood comes over me, much lighter, freer, and everything seems to be happier and more gratifying. Music is, after all, a goodly portion of my life, and when it is missing, it seems to me that all my physical and spiritual elasticity is gone.” This confession of Clara Schumann to her diary resonates, I think, with the experience of many musicians just as the impact of her musicianship and her approach to the piano recital continues to reverberate today. Angela Hewitt’s program could have been planned and performed by her musical forebearer, filled as it is by the music that Clara Schumann held most dear and brought into public awareness, championing it in her recitals more than a century ago.

Though one of the greatest keyboard virtuosi of the eighteenth century, Domenico Scarlatti’s music might have been forgotten without Schumann and her circle. She often performed his sonatas and edited a collection of them for publication. Scarlatti spent much of his career working at the Portuguese and Spanish courts, giving music lessons to noble children and performing improvised keyboard sonatas in the apartments of his royal patrons, especially his long-time student Maria Barbara, Queen of Spain, who Scarlatti asserted “[could] surprise the amazed intelligence of the most excellent Professors with her Mastery of Singing, Playing, and Composition.” Except his 30 Essercizi¸ very few of Scarlatti’s pieces appeared in print during his life, but near the end of his life he supervised the collection of polished versions of his more than 500 keyboard sonatas into manuscripts, gifts to Maria Barbara. Scarlatti loved to incorporate the sounds of popular music into his compositions – the percussive dissonance of Spanish guitar strumming and “the melodies of tunes sung by carriers, muleteers, and common people,” according to eighteenth-century music writer Charles Burney. In the preface to his Essercizi, Scarlatti described his approach to composition as “ingenious jesting with art.” Schumann’s colleague, pianist and conductor Hans von Bülow, viewed Scarlatti’s sonatas as aesthetic antecedents to Beethoven’s because in them “humour and irony set foot for the first time in the realm of sound.”

Felix Mendelssohn and Clara Schumann partnered to perform the keyboard works of J.S. Bach at the Leipzig Gewandhaus, where they had never been heard before, though Bach had worked in Leipzig only a century earlier. Schumann was one of the first concert pianists to regularly program the works of Bach and Beethoven, and her repertoire during the year 1859 included several movements from Bach’s English Suites. Likely Bach’s first set of dance suites for harpsichord, the English Suites look backward to the keyboard style of earlier German composers and to French music by Jean-Baptiste Lully and Charles Dieupart for inspiration, but they also incorporate Bach’s characteristic elaborate counterpoint, unusual in dance music. The origin of “English” in the title of these suites is perplexing, since their dances are French, and their preludes imitate Italian concertos. Perhaps the reference is to Dieupart, a Frenchman who spent much of his career in London. Bach encountered his music as a teen, when he roomed with young aristocrats attending the Ritter-Akademie in Lüneburg, who were schooled in all the high fashions of French culture. Formal French balls became so popular in eighteenth-century Germany that even middle-class citizens took dance lessons and participated in costumed balls organized by their dancing masters. Bach’s keyboard suites are like musical memories of lavish dance parties. Suite No. 6 is the grandest of the English Suites and the crown of the collection.

The close, life-long relationship between Clara Schumann and Johannes Brahms is well-known. She first performed his music in her 1854-1856 concert tours soon after she met him. Brahms had stayed with the Schumann family for some time in 1853, and Robert Schumann, composer and trend-setting music critic, had abruptly launched Brahms’ musical career by declaring in an editorial that it was as if young Brahms had “sprung like Minerva fully armed from the head of the son of Cronus.” Brahms shared Clara Schumann’s admiration for the music of Scarlatti and Bach. He collected several editions of Scarlatti’s music in his personal music library, studied it thoroughly, and quoted it in his Trio in B Major, Op. 8, probably in homage both to Scarlatti and Schumann. Like Scarlatti, Brahms synthesized folk songs and dance music idioms with art music. Of his love of Bach, Clara Schumann wrote to a friend that Brahms “played Bach almost all the time… One can wish for nothing better than to listen to such music so gloriously played.” He absorbed Bach’s contrapuntal mastery and his ability to play with short motives, turning them upside-down, inside-out, and backwards to build an entire movement from a small musical idea. One example of Brahms’ exploration of a musical motive in his Sonata in F Minor, No. 3, Op. 5, is his use of the ominous four-note “fate motive” of Beethoven’s Symphony No. 5.

At first it sneaks in as a left-hand accompaniment near the beginning of the first movement, then only the rhythm appears in the middle of the second movement without the motive’s characteristic melodic shape. Listen for it knocking deep in the bass in the middle trio section of the third movement. In the fourth movement, titled “Rückblick” or “Backwards Glance”, the motive pervades the texture and moves at a frantic pace. It is as if Brahms has expressed in music his fear that his fate – the tremendous pressure of composing in a musical tradition that included such greats as Bach and Beethoven – would consume him.

Clara Schumann did not share Brahms’ anxious relationship to music of the past. When he encouraged her to give up the taxing life of a performer for the sake of her heath, she reminded him of her profound internal motivation to bring the music of the past to audiences of the present. “You regard it only as a way to earn money. I do not. I feel a calling to reproduce great works… as long as I have the strength to do so… The practice of art is, after all, a great part of my inner self. To me, it is the very air I breath.” Musicians like Angela Hewitt continue to carry the torch of commitment to sharing passion and beauty.

- Notes by Christina Hutten

Angela Hewitt, piano

Angela Hewitt occupies a unique position among today’s leading pianists. With a wide-ranging repertoire and frequent appearances in recital and with major orchestras throughout Europe, the Americas and Asia, she is also an award-winning recording artist whose performances of Bach have established her as one of the composer’s foremost interpreters. In 2020 she received the City of Leipzig Bach Medal: a huge honour that for the first time in its 17-year history was awarded to a woman.

In September 2016, Hewitt began her ‘Bach Odyssey’, performing the complete keyboard works of Bach in a series of 12 recitals. The cycle was presented in London’s Wigmore Hall, New York’s 92nd Street Y, and in Ottawa, Tokyo and Florence. After her performances of the complete Well-Tempered Clavier at the 2019 Edinburgh Festival, the critic of the London Times wrote, “…the freshness of Hewitt’s playing made it sound as though no one had played this music before.”

Hewitt’s award-winning cycle for Hyperion Records of all the major keyboard works of Bach has been described as “one of the record glories of our age” (The Sunday Times). Her discography also includes albums of Couperin, Rameau, Scarlatti, Mozart, Chopin, Schumann, Liszt, Fauré, Debussy, Chabrier, Ravel, Messiaen and Granados. The final CD in her complete cycle of Beethoven Sonatas (Op.106 and Op.111) will be released in 2022. A regular in the USA Billboard chart, her new album Love Songs hit the top of the specialist classical chart in the UK and stayed there for months after its release. In 2015 she was inducted into Gramophone Magazine’s ‘Hall of Fame’ thanks to her popularity with music lovers around the world.

Conducting from the keyboard, Angela has worked with many of the world’s best chamber orchestras, including those of Salzburg, Zurich, Lucerne, Basel, Stuttgart, Sweden, and the Britten Sinfonia. One recent highlight was her debut in Vienna’s Musikverein, playing and conducting Bach Concertos with the Vienna Tonkünstler Orchestra. In 2021/22 concerto performances include the Royal Stockholm Philharmonic, Helsinki Philharmonic and Toronto Symphony orchestras, Orchestra Ensemble Kanazawa and Concerto Budapest (UK tour), while recitals take place in London, Rome, Leipzig, Dortmund, Tallinn, New York, Philadelphia and Tokyo, among many others. In July 2022 Angela is Chairman of the Jury of the prestigious International Bach Competition Leipzig.

Her frequent masterclasses are hugely appreciated. When all concert activity abruptly stopped in spring 2020 due to the pandemic, Angela went online to share daily offerings of short pieces—many of which form the basis of teaching material. Her fans were thrilled, and she was happy to inspire them and stay in touch.

Born into a musical family, Hewitt began her piano studies aged three, performing in public at four and a year later winning her first scholarship. She studied with Jean-Paul Sévilla at the University of Ottawa, and won the 1985 Toronto International Bach Piano Competition which launched her career. In 2018 Angela received the Governor General’s Lifetime Achievement Award, and in 2015 she received the highest honour from her native country – becoming a Companion of the Order of Canada (which is given to only 165 living Canadians at any one time). In 2006 she was awarded an OBE from Queen Elizabeth II. She is a member of the Royal Society of Canada, has seven honorary doctorates, and is a Visiting Fellow of Peterhouse College in Cambridge. In 2020 Angela was awarded the Wigmore Medal in recognition of her services to music and relationship with the hall over 35 years.

Hewitt lives in London but also has homes in Ottawa and Umbria, Italy where fifteen years ago she founded the Trasimeno Music Festival – a week-long annual event which draws an audience from all over the world.