Chan Centre for the Performing Arts

Mélisande Corriveau, pardessus; Eric Milnes, harpsichord

The works selected by Mélisande Corriveau and Eric Milnes for this evening present a vibrant array of French musical styles developed during the 18th century before the French Revolution. The origin and development of the pardessus de viole – known in France as “the woman’s violin”- coincided with the increasing prominence of the violin in French instrumental fashion. The crowning glory of the viola da gamba family, the pardessus – the smallest of the viola da gamba family of instruments – facilitated the instrument’s rise in popularity in France. Most of the works which will be performed were selected from the microfilm collections of the Bibliothèque Nationale de France, and few had been recorded until Mélisande’s recent recording. They are charming, playful, luminous and exquisitely elegant.

Please note, this concert will be filmed

Programme

Louis de Caix D’Hervelois (1680-1759)

Suite en ré mineur │ Suite in d minor

Ve livre de pièces pour un pardessus de viole A Cinq et Six cordes avec la Basse, Xe Oeuvre (1753)

5th volume of pieces for a pardessus de viole with five and six strings with Bass, Opus 10 (1753)

Prélude

La Tourolle

La Diligence

Sarabande

La Légèreté

Menuets 1, 2 et 3

Jean Bodin de Boismortier (1689-1755)

Deuxiéme sonate, sol mineur │ Second Sonata in g minor

Oeuvre soixante-uniéme contenant VI sonates Pour le Pardessus de Viole Avec la Basse (1736)

Opus 61 including six sonatas for the Pardessus de Viole with Bass (1736)

Gravement

Courante

Rondeau Gracieusement

Gigue

Charles Dollé (c.1710-c.1755)

Pièces tirées de l’Oeuvre IVe│ Pieces from Opus Four

Sonates, Duo & Pièces Pour le pardessus de viole, Livre Second (1737)

Sonatas, Duo and pieces for the pardessus de viole, Second volume (1737)

La Favoritte (Tendrement)

Les Regrets (Affectueusement)

Sonata I, la mineur │ Sonata 1 in a minor

Adagio

Allegro ma non tropo

Sarabanda

Giga Allegro

Jean-Sébastien Bach (1685-1750)

Trio Sonata No 3 in d minor, BWV 527

Transcribed from Organ Sonata

Andante

Adagio e dolce

Vivace

The pardessus de viole used for this concert is a rare exemplar, dated 1755, from the workshop of Pierre LePilleur, Paris ,“faiseurs d’instruments for the Musketeers”.

Program Notes

The pardessus de viole

the “woman’s violin”

The works selected for this concert present a vibrant array of French musical styles, which developed, intermingled, and competed for the favor of both connaisseurs in the salon, and the public at such venues as the Parisian Concert Spirituel, during the eighteenth century until the Revolution. The origin and development of the pardessus de viole, that instrument known in France as “the woman’s violin,” coincided with the increasing prominence of the violin in French instrumental fashion. Of particular interest is the pardessus’ status as the final accrual to the beauteous viola da gamba family to enjoy great popularity in France.

Most of the works performed here are unpublished. They were selected from the microfilm collections of the Bibliothèque Nationale de France. At the time of their composition, they catered to a large public, responding to widespread demand for refined entertainment. They are without exception charming, playful, luminous, and exquisitely elegant.

A brief history of the pardessus de viole

The smallest member of the viola da gamba family, the pardessus de viole was designed to meet the expressive needs of French society, was continually modified, and was ultimately abandoned. The instrument’s history is intriguing: its idiomatic repertoire spans a mere half century, although the instrument itself was in wide use for over a hundred years. Despite this brief appearance in the evolution of Western art music, it is the subject of a remarkably rich history, and many of the most distinguished viol players of the period performed on it. Composers of distinction wrote very beautiful music for it, and highly-skilled luthiers created marvelous exemplars, some of which survive to this day.

The pardessus originated in France at the end of the seventeenth century, as the viola da gamba (both dessus or treble, and bass) had reached the pinnacle of a fertile period as a solo and chamber instrument, and firmly occupied a place of privilege in music and spectacle at the court of Louis XIV. Because the Roi Soleil himself loved and cherished the viola da gamba throughout his reign, his noblemen and courtiers showed a singular interest in it. This interest was revitalized with the introduction of the new member of the viol family, the pardessus.

What exactly was this new instrument? The pardessus, as its name indicates – the literal translation is: higher than the treble. The first pardessus viols were small trebles, differently strung. Eventually, luthiers of the École des Vieux Paris (notably Collichon and Bertrand) endowed it with its own frame, a smaller soundboard, and proportionally smaller components.

During the first twenty years following its appearance, the precise role of the pardessus in musical life is obscure. In the absence of any repertoire of its own during those years, music written for other treble instruments, including the newly-emergent violin, was appropriated to its use. The violin, present in France from the sixteenth century, was regarded as the emblematic Italian instrument and was mainly associated with the lower classes, suited to dance or strolling, and appropriate to light entertainment. More serious and refined music was, therefore, reserved for the viol family, which held a more prominent role in music at court. The dazzling success of Arcangelo Corelli’s (1653-1713) violin sonatas, as well as performances by Italian virtuosi in France, would incite French composers – or sonatistes – to write for the violin. Esteem for this instrument rose to a point where it eventually entered a golden age that coincided with the popularity of the new sonata form. Passionate debates ensued between Italianist enthusiasts and French purists. This dichotomy caused the viol to be associated with a certain Ancien Régime conservatism, whereas violin-wielding Italianists considered themselves as more modern, free thinkers.

The violin’s early reputation as a “lowly instrument” made it unsuitable for performance by members of French high society, particularly noblewomen – a bias that persisted throughout the mid-eighteenth century. Proponents of the older French style remained faithful to traditional viol practice. Many of them excelled at the bass viol and the dessus, and thus a transition to pardessus would have been much more straightforward than attempting a whole new type of instrument such as the violin. Because of its range, mastery of the pardessus resulted in easier access to the growing violin repertoire, and in the mid-eighteenth century it had become the “woman’s violin”. As François-Alexandre-Pierre de Garsault wrote in 1761, “Ladies hardly ever play the violin whereas the pardessus de viole may serve in its place since it is capable of playing nearly everything that may be executed on the violin”. Viols were especially popular with women and belonged to the category of “feminine instruments,” along with the lute, the harp, and the harpsichord. Socially, these instruments enabled their players to maintain a more dignified demeanor according to norms of propriety: “…ladies shall play the treble viol with five strings and never the violin, as the position involved in playing the violin in no way suits them. While their hands are too small to hold it, they also experience endless hardship in climbing to the high positions…. which can be done easily and without shifting on the first string of the quinton as well as on the pardessus de viole with five strings”. (Michel Corrette c.1748). Ladies would also have been troubled by neck marks caused by regular violin practice, and also by the ways in which playing a da braccio instrument could compromise costly and intricate hairdressings. Over time, the popularity of the instrument is seen to have extended beyond the confines of the nobility, and musical iconography from the period clearly shows bourgeois women adopting its use, demonstrating the instruments’ broader appeal.

Repertoire specifically composed for pardessus began to appear in the 1720s. The introduction of a five-string pardessus in the 1730s (or 1740s, depending on opinion) ushered in a period of great popularity for the instrument (1730-1770). The pardessus was subjected to a series of transformations during this time: the removal of a string, the narrowing of the soundboard and other refinements to the neck rendered it visually similar to the violin, but a deeper commonality is found in the respective instruments’ tuning: from lowest to highest note, G-D-A-D-G on the five-string pardessus and G-D-A-E on the violin. Tuning in fifths on the lower three strings of the pardessus further opened up the instrument to the violinistic repertoire. Although removing a string did nothing to change the instrument’s range, it did free the soundboard of considerable pressure, resulting in a more resonant, pure, and flute-like sound. The link between pardessus and violin is clearly demonstrated by the existence of publications citing the interchangeable use of one instrument or the other. We see at this time a vast increase in the number of idiomatic works for the five-string pardessus. For its part, the six-string pardessus remained in use for many years, although it’s tuning, which includes a central major third, is less practical when playing music written for violin.

In the early 1760s, a four string pardessus was conceived with the object of imitating perfectly violinistic effects. Although no specimen has survived, evidence suggests it was simply a violin held vertically. Posuel de Verneaux reported in 1766 that “In Paris, many people play the pardessus de viole with four strings, the fingering and tuning being similar to that of a violin…”

In the 1770s French composers continued to write for the pardessus until the instrument fell out of use by the end of the eighteenth century.

Seen in retrospect, the pardessus’s physical resemblance to the violin resulted in its loss of singularity, and consequently, its raison d’être. Concurrently, evolving trends in public concerts favoured the instrument less and less, relegating it to the salon. Finally, a relaxing of attitudes concerning the etiquette of da braccio playing of the violin, and its appropriateness for polite society, further accelerated the demise of the pardessus. It would be abandoned even by its most loyal defenders: the nobility, women, and bourgeois intellectuals who would come to know the dark times of the Revolution (1789) and would soon witness the destruction of “instruments of entertainment” at the hands of revolutionists.

- Mélisande Corriveau

Mélisande Corriveau, pardessus

A specialist in early-music performance, multi-instrumentalist Mélisande Corriveau has been praised for her exceptional musical mastery. She is frequently a guest at major festivals in both North America and Europe, and is an active concert, touring, and recording artist. She regularly performs with a number of celebrated ensembles, and is a member of the ensembles Masques (France), Les Voix humaines, Sonate 1704, and Les Boréades de Montréal. As a soloist, she has been featured with Les Violons du Roy, National Art Center Orchestra, Montreal Symphony Orchestra,Tafelmusik Baroque Orchestra, and has toured with Jordi Savall and Ensemble Hespèrion XXI. Her discography comprises some 50 titles on various labels. Her discs with harpsichordist Eric Milnes - Pardessus de viole and Marin Marais : Badinages - have won numerous accolades including Opus Prizes for early-music CD of the year and classical disc of the year by ICI Radio- Canada (2016). Mélisande Corriveau and her partner Eric Milnes co-direct the two time Juno award-winning vocal and instrumental ensemble L’Harmonie des saisons, which they founded in 2010. In 2014, Ms. Corriveau completed, with honors, a doctorate in pardessus de viole performance at the Université de Montréal. She is recognized as one of the world’s few specialists on this instrument.

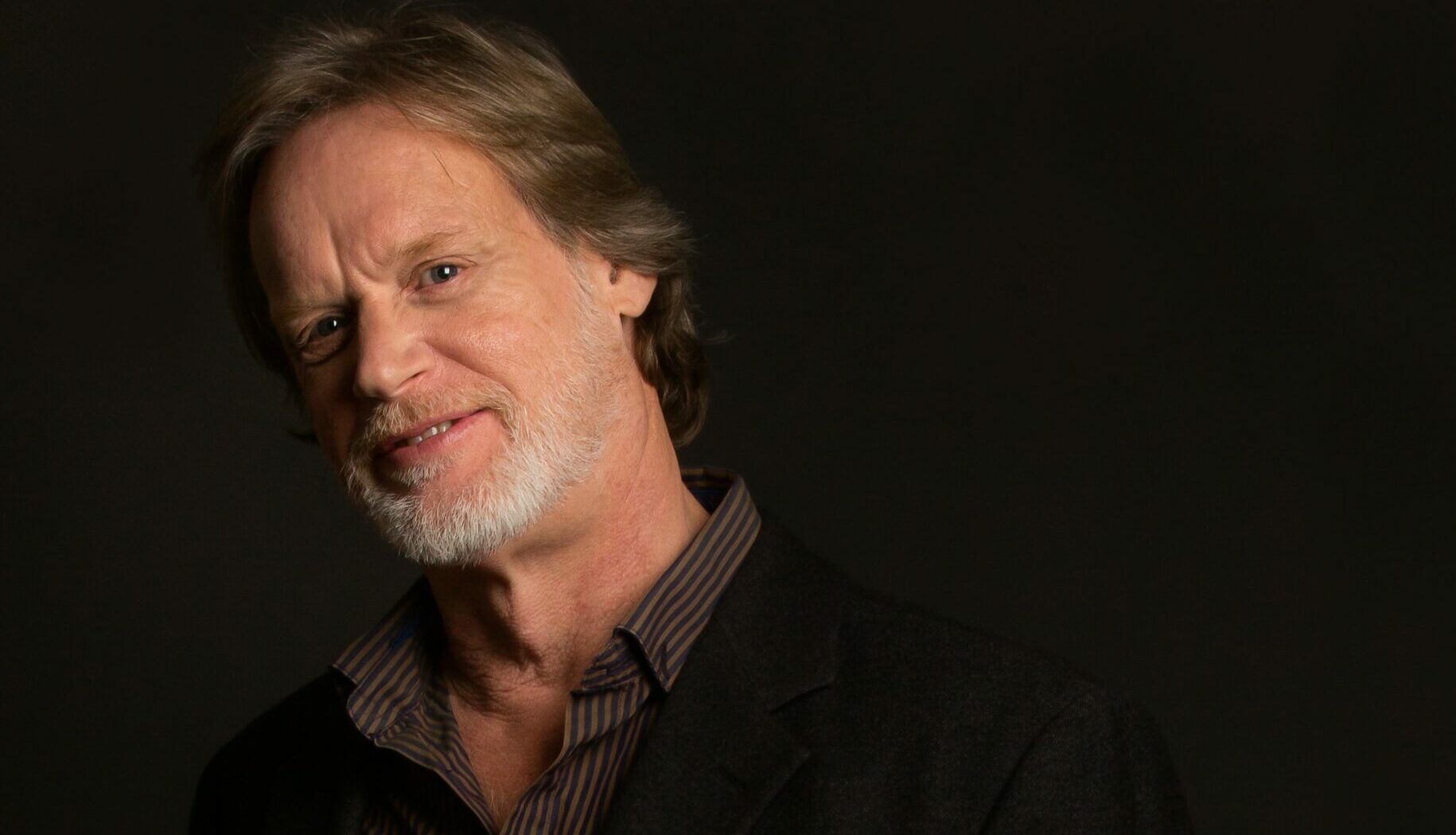

Eric Milnes, harpsichord

Eric Milnes has been critically acclaimed throughout North America and Europe as one of the most dynamic and compelling early music directors and keyboard artists of the younger generation. A native New Yorker, his imaginative and energized performances have been applauded at the Utrecht, Bremen, Regensburg, Lufthansa, Passau, Boston, Mostly Mozart, Montreal, Vancouver, Ottawa, Berkeley, Santa Fe and San Francisco Early Music Festivals, and in performances in every major North American and European center. As conductor he has directed New York Baroque, The New York Collegium, Trinity Consort, Portland, Oregon, The Northwest Chamber Orchestra, Seattle, I Cantori di New York, Musica Divina, Ottawa, Les Boreades de Montreal, La Bande Montreal Baroque, and Baroquen Voices, Montreal.

As harpsichordist and organist, he has recorded and/or performed with Gustav Leonhardt, Reinhard Goebel, Fabio Biondi, Christophe Rousset, Martin Jester, Andrew Parrott, Manfredo Kraemer, Barthold Kuikjen, Les Voix humaines, Ensemble Rebel, Les Boreades, The American Bach Soloists, and ensembles across North America. Recordings under his direction include Hebrew motets of Salamone Rossi, vocal cantatas of Barbara Strozzi, sacred music of Heinrich Schütz, vocal chamber music of Ristori from Dresden, Handel’s Acis and Galatea, The St. John Passion of Bach, and Bach Sacred Cantatas. A published composer, Mr. Milnes has served with the faculty of several universities and conservatories in New York and in Norway. His degrees are from Columbia University, New York, and The Juilliard School, New York.