Roy Barnett Recital Hall | Map

Early Music Vancouver Mentorship Orchestra

Our Festival this year includes the first instance of an exciting new initiative. We’ve created a Mentorship Orchestra Project, in which students of exceptional ability receive free tuition and housing, and one-on-one coaching from some of the most prominent instrumentalists in their field. The culmination: after five days of intensive work on Haydn’s early symphonies – “Le Matin,” “Le Midi,” and “Le Soir” – these up-and-coming artists will perform with the faculty and other renowned professional artists in this extraordinary Festival concert.

Mahony and Sons is proud to sponsor Early Music Vancouver. Join us before or after your concert and make your experience a great one. For reservations visit mahonyandsons.com. We validate parking at our UBC location.

Programme

Symphony no. 6 “Le matin” H. 1/6, Franz Joseph Haydn (1732-1809)

I. Adagio – Allegro

II. Adagio – Andante – Adagio

III. Menuetto e Trio

IV. Finale: Allegro

Symphony no. 7 “Le midi” H. 1/7

I. Adagio – Allegro

II. Recitative – Adagio

III. Menuetto e Trio

IV. Finale: Allegro

Intermission

Symphony no. 8 “Le soir” H. 1/8

I. Allegro molto

II. Andante

III. Menuetto e Trio

IV. La Tempesta: Presto

Harpsichord concerto in D-major Hob.XVIII:11

I. Vivace

II. Un poco adagio

III. Rondo all’Ungarese: Allegro assai

Programme notes

It all started rather innocently as a way for Italian Baroque opera composers to quiet the rambunctious audience members anxiously awaiting the start of the opera. Brief three-part sinfonias or opera overtures, as they also came to be known, were eventually lengthened and made more substantial, giving birth to a new genre: the symphony. Although Franz Joseph Haydn cannot be given single-handed credit for the creation of the symphony, he certainly helped propel the genre forward, and not only for having written over 100 of them. Known for his originality as much as his sheer quantity of compositional offspring, Haydn solidifies a path set in motion by early opera composers illustrating the ability of expressing drama in instrumental music even without singers. By the end of the 18th century, the symphony became the single most important genre of orchestral music and helped pave the way for instrumental music from the Baroque into the Classical era and beyond.

The earliest true symphonies were exponents of the galant style that emerged in the third quarter of the 18th century, the period between the High Baroque and Viennese Classicism. Galant style is in many ways a reaction to the ornamented, more highly polyphonic, more harmonically diverse and complicated music of the Baroque that features a return to simplicity of melodic lines, harmony, and structure. Chief composers of this period included Sammartini, and two of J.S. Bach’s sons, C.P.E. Bach and Johann Christian Bach. The influence of C.P.E. Bach cannot be underestimated and realizing Bach’s son’s connection to Haydn helps us enjoy the progression from the Baroque era to the future by passing on knowledge from the past. Taken from A.C. Dies’ Biographische Nachrichten von Joseph Haydn (Vienna, 1810), we learn how personal their connection was:

“Haydn ventured into a bookshop and asked for a good textbook on theory. The bookseller named the writings of Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach as the best and most recent. Haydn wanted to look and see for himself. He began to read, he understood, found what he was looking for, paid for the book, and took it away thoroughly pleased.

As soon as Haydn’s musical output became available in print, C.P.E. Bach noted with pleasure that he could count Haydn among his pupils. He later paid Haydn a flattering compliment; that Haydn alone had understood [Bach’s] writings completely and had known how to make use of them.

Haydn lived at a time when aristocratic patronage was a necessity for a composer to survive and in 1757, at the age of 25, he received his first full-time appointment as Kappelmeister for Count Morzin. This new stability was relatively short-lived, however, as the Count fell upon hard times financially and Haydn’s position was one of the casualties. Luckily, as is often the case in a musician’s employment, Haydn was at the right place at the right time when Prince Paul Anton Esterházy happened to witness one of Haydn’s performances at the Bohemian summer home of Count Morzin. Haydn must have made quite an impression because when the Prince heard of his situation, he quickly offered him the position of Deputy Kappelmeister for a newly expanded orchestra at his own court at Eisenstadt, south of Vienna. Musical life was extremely important to the Prince and not only did he competently play several instruments himself, but it was a priority to employ some of the leading virtuosi of the day in his court orchestra. Haydn signed the contract with the Esterházy court in May of 1761 and thus began one of the most prolific situations of musical patronage in all of music history, lasting almost exactly 30 years.

Apparently, no time was wasted and Haydn got to work writing the three symphonies you will hear tonight, a trilogy often referred to as Die Tageszeiten (The Times of the Day). These symphonies were completed early in 1761 and his new position afforded him the opportunity to run a veritable musical laboratory. He is oft-quoted as describing his working life as such:

As head of an orchestra I could experiment, observe what heightened the effect and what weakened it, and so could improve, expand, cut, take risks. I was cut off from the world, there was no one near me to torment me or make me doubt myself, and so I had to become original.

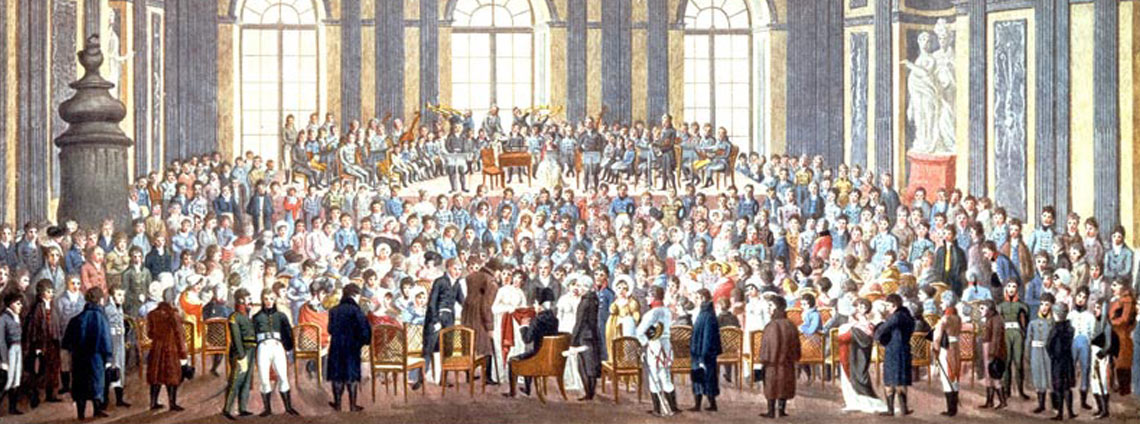

Prince Esterházy spent some time in Naples in a diplomatic capacity and came away from that experience with Italian taste in music. His collection of Italian music included Vivaldi’s set of violin concerti known as ‘The Four Seasons’. It has been suggested that the Prince mentioned to Haydn that he should compose a similar set of pieces inspired by the different times of the day that demonstrate, according to H.C. Robbins Landon, his “uncanny ability to write music that pleased the patron and yet was uncompromising in its technical, formal and instrumental level of standards.” The first performances of the trilogy of symphonies were likely performed in the great hall of the Esterházy’s Viennese palace, the court’s summer residence, in May or June of 1761.

Symphony No. 6 ‘Le matin’ or ‘Morning’ begins with a slow introduction representing the awakening of the sun, followed by entrances of the flute and oboe evoking the pleasant chirping of birds responding to the dawning of a new day. This develops into moments of virtuosity for the entire ensemble, undoubtedly written to highlight not only Haydn’s compositional creativity but also the exceptional orchestra hired for the court’s entertainment. The second movement is more of a Corelli-inspired Baroque concerto for violin and cello than merely a symphony movement. The bass and bassoon are featured during the trio of the Minuet, with a return to the ensemble virtuosity for the Finale.

The 7th Symphony, ‘Le midi’ or ‘Noon’ begins with another slow introduction which soon becomes more feverish activity as two violins and cello take over with the energized sense of purpose of mid-day. The second movement begins as a song without words for the violin by using the operatic device ‘recitativo accompagnato’ or accompanied recitative, another Italianate styling which surely pleased the Prince. The lower voices are once again in the spotlight for the Minuet and Trio, followed by a return to the fierce activity of the opening movement to close out the symphony.

As musicologist Daniel Heartz discovered in 1981, the opening melody of Symphony No. 8, ‘Le soir’ or ‘Evening’, is identical to a song from Gluck’s French comic opera Le diable à quatre (approximately, “The Devil to Pay”), performed in Vienna in 1759. The words of this song are quite cheeky: “I don’t like tobacco very much, I don’t use it much, often not at all, but my husband objects. Presently, I find it tempting, if I take a little when alone, because it relieves boredom, no matter what my husband says.” It is likely Prince Esterházy saw the opera in Vienna and requested for Haydn to use it in his new set of pieces. The second movement, like the others, is another moment for the soloists to shine, starting with the violins, then cello, followed by bassoon. The Minuet features the woodwinds, with another bass spotlight for the Trio. For the final movement, the rapid succession of repeated notes in the violin and cello suggests the rumble of thunder during an evening storm, while the flute can be seen as either delivering lightning strikes or falling arpeggiated raindrops as an evocative ending to the evening. – Kris Kwapis