Chan Shun Concert Hall at the Chan Centre for the Performing Arts | Map

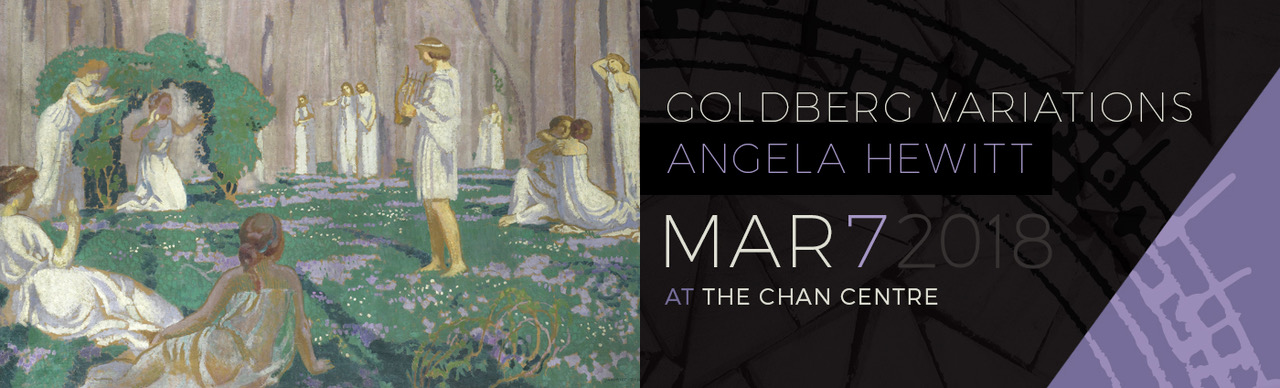

One of the world’s leading pianists, Angela Hewitt regularly appears in recital and with major orchestras throughout Europe, the Americas and Asia. Her performances and recordings of Bach have drawn particular praise, marking her out as one of the composer’s foremost interpreters of our time. Join EMV for a continuation of our Goldberg Experience and for another perspective on Bach’s iconic work played by a national treasure.

“It was a positive sensation. The Canadian pianist is one of the reliably mesmerising musicians of the day. You sit entranced… it would have been more accurate to say I was floating just below the ceiling.” – The Sunday Times

This concert will be preceded by a discussion with Ian Alexander

This concert is being recorded by CBC Music for future broadcast on In Concert, heard Sundays from 11 am to 3 pm with host Paolo Pietropaolo.

Supported by Ingrid Söchting & Douglas Todd and Dr. Katherine E. Paton

Programme

Please note that this programme will be performed without an interval

1 Aria

2 Variation 1: a 1 Clav.

3 Variation 2: a 1 Clav.

4 Variation 3: Canone all’Unisuono. a 1 Clav.

5 Variation 4: a 1 Clav.

6 Variation 5: a 1 ô Vero 2 Clav.

7 Variation 6: Canone alla Secunda. a 1 Clav.

8 Variation 7: a 1 ô Vero 2 Clav. Al tempo di Giga

9 Variation 8: a 2 Clav.

10 Variation 9: Canone alla Terza. a 1 Clav.

11 Variation 10: Fughetta. a 1 Clav.

12 Variation 11: a 2 Clav.

13 Variation 12: Canone alla Quarta. a 1 Clav.

14 Variation 13: a 2 Clav.

15 Variation 14: a 2 Clav.

16 Variation 15: Canone alla Quinta. a 1 Clav. Andante

17 Variation 16: Ouverture. a 1 Clav.

18 Variation 17: a 2 Clav.

19 Variation 18: Canone alla Sexta. a 1 Clav.

20 Variation 19: a 1 Clav.

21 Variation 20: a 2 Clav.

22 Variation 21: Canone alla Settima. a 1 Clav.

23 Variation 22: a 1 Clav.

24 Variation 23: a 1 Clav.

25 Variation 24: Canone all’Ottava. a 1 Clav.

26 Variation 25: a 2 Clav. Adagio

27 Variation 26: a 2 Clav.

28 Variation 27: Canone alla Nona. a 2 Clav.

29 Variation 28: a 2 Clav.

30 Variation 29: a 1 ô Vero 2 Clav.

31 Variation 30: Quodlibet. a 1 Clav.

32 Aria da capo

Programme Notes

Throughout his years as Cantor of the St Thomas School in Leipzig (1723–1750), Johann Sebastian Bach had to struggle with the musical ignorance of his superiors to whom, upon taking up the post, he had pledged respect and obedience. The city council was apparently unable to appreciate the marvelous things Bach was doing for the musical life of Leipzig, and constantly denied him the improvements he requested and desperately needed. The situation became so frustrating for him that in October 1730 he wrote to his boyhood friend Georg Erdmann (at the time agent of the Emperor of Russia in Danzig) asking for help in finding another position. He told Erdmann that since taking up the directorship in Leipzig: “I find that the post is by no means so lucrative as it was described to me; I have failed to obtain many of the fees pertaining to the office; the place is very expensive; and the authorities are odd and little interested in music, so that I must live amid almost continual vexation, envy, and persecution; accordingly I shall be forced, with God’ s help, to seek my fortune elsewhere.”

We have no trace of a reply to this letter, and Bach remained in Leipzig for the rest of his life. He did, however, seek the title of ‘Court composer to the King of Poland and the Elector of Saxony’ by dedicating the Kyrie and Gloria of his B minor Mass to King Frederick Augustus in 1733. The title was eventually granted him in 1736, largely due to the intervention of Hermann Carl, Baron von Keyserlingk.

Count Keyserlingk (as he later became) was the Russian ambassador to the court of Dresden, appointed by Catherine the Great. Music was his passion, and at his home in Neustadt he gathered around him some of the best instrumentalists of his day, among them a prodigious young harpsichordist named Johann Gottlieb (or Theophilus, which he preferred) Goldberg. Born in Danzig (Gdańsk) in 1727, Goldberg studied with Bach’ s eldest son, Wilhelm Friedemann, in Dresden, but then was sent to Leipzig by Count Keyserlingk to study with Bach himself in the early 1740s. His fame as a virtuoso quickly spread, and it was recounted that he could read anything at sight—even if the score was upside down! Bach must have delighted in having such a pupil.

The circumstances under which the ‘ Goldberg’ Variations came into being were passed down to us by Bach’ s first biographer, Johann Nikolaus Forkel. In 1802 he wrote:

The Count [Keyserlingk] was often sickly, and then had sleepless nights. At these times Goldberg, who lived in the house with him, had to pass the night in an adjoining room to play something to him when he could not sleep. The Count once said to Bach that he should like to have some clavier pieces for his Goldberg, which should be of such a soft and somewhat lively character that he might be a little cheered up by them in his sleepless nights. Bach thought he could best fulfill this wish by variations, which, on account of the constant sameness of the fundamental harmony, he had hitherto considered as an ungrateful task. But as at this time all his works were models of art, these variations also became such under his hand. This is, indeed, the only model of the kind that he has left us. The Count thereafter called them nothing but ‘ his’ variations. He was never weary of hearing them; and for a long time, when the sleepless nights came, he used to say: “Dear Goldberg, do play me one of my variations.” Bach was, perhaps, never so well rewarded for any work as for this: the Count made him a present of a golden goblet filled with a hundred Louis d’ors. But their worth as a work of art would not have been paid if the present had been a thousand times as great.

Some musicologists don’ t quite believe Forkel’ s tale for several reasons. First of all, the work carried no dedication when it was published in 1742. Bach simply entitled it Keyboard Practice, consisting of an Aria with Diverse Variations, for the Harpsichord with 2 Manuals. Composed for Music Lovers, to Refresh their Spirits (as Glenn Gould said, ‘a very down-to-earth description of such a great work’ ). Secondly, Goldberg would have been only fourteen or fifteen years old at the time—but surely there were prodigies then as there are now. Had he not died at the age of twenty-nine, we might have known more about its inception. Finally, no gold goblet was mentioned in Bach’s estate, although there was a tobacco box of agate set in gold which was very highly valued. Whether or not it is true doesn’t really matter. It remains a good story (and a good title!), and one which no doubt will forever be attached to this monumental work.

The Aria that Bach uses as the theme for his variations appears in the notebook of pieces he began collecting for his second wife, Anna Magdalena, in 1725. Until recently it was thought to have existed for at least ten years before Bach chose it as his theme, but musicologists now think it was written expressly for the purpose and copied into two spare pages of the notebook. This is largely irrelevant; what is important is its character and rhythm—that of a dignified, stately sarabande, full of tenderness and poise. It is highly embellished in the French manner—meaning that the ornaments are an essential part of the melodic line, not optional extras. Rather than the melody, however, it is the bass line, or more specifically the harmonies which it implies, that is used as a basis for the thirty variations which follow. Throughout, we have the same overall harmonic structure of four 8-bar phrases (or 4-bar phrases depending on the time signature): the first establishes the tonic of G major; the second moves to the dominant; after the double bar (repeat) it moves from the dominant to the relative (E minor), increasing the tension, before returning home to the tonic in the final 8 bars (after which the second half is repeated). Three variations are in G minor, where E flat major is substituted for E minor, adding some light to the darker mode (except in the remarkable Variation 25 which remains sombre by passing through E flat minor).

On this solid base, Bach builds a magnificent edifice that is both beautifully proportioned and astonishingly varied. The variations are organized into groups of three, with every third variation being a canon. In these, the upper two voices engage in exact imitation, beginning at the unison in Variation 3, and moving up step by step so that Variation 27 is a canon at the ninth. They are among the most vocal in character of the variations, and are so ingeniously put together that we can listen to them without thinking of their construction, although that of course adds to our enjoyment and intellectual stimulation. Each group begins with a free variation (often akin to a dance but still very contrapuntal). The second of the set is a toccata for two keyboards, with the most brilliant variations belonging to this group. Here, Goldberg would really have had the chance to show off his virtuosity.

Variation 1 sets the joyous tone that is characteristic of so much of this work. Both the leaps and the rhythm of the left hand in the first bar are motifs for joy in Bach’s music (as in the A flat major Prelude from Book I of The Well-Tempered Clavier). This two-part invention already gives us a taste of the hand-crossing that will be such a feature in later variations. The one exception to the pattern of toccatas is Variation 2, which teases us at the beginning by almost being a canon. It is a simple three-part invention, similar to the Little Prelude in D major, BWV936, with two voices engaging in constant dialogue over a running bass. Perhaps Bach realized that we needed a bit more time to warm up before engaging in high jinks! Then comes the first of the canons in Variation 3—this one at the unison (the upper voices beginning on the same note, one bar apart). The time signature of 12/8 hints at a mood of pastoral simplicity with a touch of the dance. With the canonic voices being so close together, and played with the one hand, it is a challenge to distinguish them enough for the listener to be able to comprehend their constant crossings (this of course applies more to the piano than to the harpsichord). In the first four bars the left hand sets out the harmonies simply and gracefully, but then gets more involved in filling out the texture.

A rustic-sounding dance in 3/8 time makes up Variation 4. The opening three notes constantly jump from voice to voice in playful imitation with syncopations adding extra interest. It sets us up perfectly for the first of the brilliant toccatas. Variation 5 uses the Italian type of hand-crossing, where one hand makes dangerous leaps over the other. The left hand is the first to have a go, soon followed by the right as Bach typically inverts the counterpoint. It is, as Wanda Landowska stated, ‘ an outburst of irrepressible joy’. Before the next toccata we have a chance to calm down. Variation 6 is a canon at the second, and what better motif for that than a descending scale? It alternates beautifully between rising and falling, and the shadowing of the leader by the ensuing voice is not without tenderness.

Although the autograph manuscript of the ‘ Goldberg’ Variations has been lost, we do have a copy of the original edition (published by Balthasar Schmid in Nürnberg) that is notated in Bach’ s own hand (Handexemplar). As it was discovered as recently as 1974, only editions published after that date take into account the findings therein. Several tempo markings are added, in particular ‘ Al tempo di Giga’ for Variation 7. Presumably Bach wanted to guard against taking too slow a tempo, thus making it a siciliano or forlana. It is, in fact, a French gigue, very similar to the one in the French Overture, BWV831. Its dotted rhythms and sharp ornaments make it one of the most attractive of the variations. Technical difficulties resume in Variation 8, with some treacherous overlapping of the hands. This is hand-crossing in the French style where both are playing at once in the same part of the keyboard. On the piano this poses singular problems and requires great care if it is not to sound confused. As in all the toccata variations, switching the odd note or passage to the other hand from which it is written certainly helps, as long as the voice-leading is still absolutely clear. The rhythm of Variation 8 can also be confusing; without seeing the score, some people will hear the beginning in 6/8 instead of 3/4 time. It is perhaps best to slightly emphasize the beats to avoid being misled. The hands alternate between moving towards or away from each other—rather like some kind of technical study—with the crossing of the arms providing visual excitement. The next canon, Variation 9, is at the interval of a third. Beautifully lyrical, flowing yet unhurried, its expressiveness is supported by a more active bass line than in the previous canons.

Variation 10 is a fughetta in four parts—very genial in nature, and reminding me of the D major March from the Anna Magdalena Notebook, also marked ‘ alla breve’ (and now thought to be composed by Bach’ s son, Carl Philipp Emanuel). More overlapping of the hands occurs in Variation 11, a gentle gigue-like toccata in 12/16 time which requires great delicacy. It makes use of crossing scales (which, even on one keyboard, must be seamless) and some capricious arpeggios and trills, the whole dissolving into thin air at the end. Then Bach gives us the first of the canons in inversion (where the second voice is in contrary motion to the first). Variation 12, a canon at the fourth, is also the first one where the voices reverse their leadership role after the double bar. I find something very regal in its character, and therefore think it shouldn’t be hurried.

This brings us to Variation 13—one of the most sublime and, I feel, something of an emotional turning-point in the work. If most of the preceding variations are fairly terrestrial, although wonderful in their dance-like rhythms, Variation 13 truly transports us for the first time. Its tender, cantabile melody, resembling a slow (but not too slow!) movement from a concerto, soars above the accompanying voices, using some violin figurations and two-note ‘ sighs’ in the cadential bars. A few chromaticisms in the left hand towards the end serve only to enhance our state of bliss. Staying in the same part of the keyboard, but with the hands exchanging places, Bach wakes us from our dream with a sharp, cheerful mordent beginning Variation 14. This same mordent is then the sole feature of a passage which takes us down the full range of his keyboard (changing to an ascent after the double bar). We are so often told that all ornaments must be executed on the beat in Baroque music, but here Bach writes them out in full before the beat. So much for the rules! After this brilliant outburst, Variation 15 presents us with a canon at the fifth and the first of the minor-key variations. I think it very fitting that it is in contrary motion, as the downward movement, with its ‘ sighing’ figures adopted from Variation 13, is very sorrowful, but its ascending counterpart brings hope. Bach was unable to accept total despair because of his deep religious faith, and this variation is a perfect example of how he expressed this in music. The tempo marking is Andante, and the time signature 2/4, so it must flow despite its sorrow. The bass line is a full participant in the drama, imitating the sighs and wide intervals of the upper voices. There is a wonderful effect at the very end: the hands move away from each other, with the right suspended in mid-air on an open fifth. This gradual fade, leaving us in awe but ready for more, is a fitting end to the first half of the piece.

The ‘Goldberg’ Variations are usually considered to be the fourth part of Bach’s Clavierübung (‘ Keyboard Practice’ ), although he didn’t specify them as such. The first volume comprised the six ‘ Partitas’ , the second the ‘ Italian Concerto’ and the ‘ French Overture’ , and the third various organ compositions along with the ‘ Four Duets’. In each of these, a French overture figures prominently: as the opening of the Fourth Partita in D major; again as the opening of the work by that name in the second volume; and as the Prelude of the E flat major Prelude and Fugue for organ, BWV552, in Part Three. In the ‘ Goldberg’ Variations, as Variation 16, it ceremoniously opens the second half with great pomp and splendour. It is in two sections: the first—very grandiose with running scales, brilliant trills and sharply dotted rhythms—takes us as far as the dominant key in bar 16. After the repeat follows a faster, fugal section as is customary in a French overture. Here the texture is much more transparent but still very orchestral, and we have two quick bars of 3/8 for each bar of the original harmony.

Variation 17 is a spirited and light-footed toccata in which Bach obviously takes great delight in writing expressly for two keyboards. On the piano the hands are playing on top of each other for a lot of the time. He continues in a good-natured mood with Variation 18, a canon at the sixth. Much of this good nature is present in the bass line which skips happily about under the two canonic voices where suspensions are the name of the game.

Variation 19 is in the style of a passepied—a delicate, charming dance in 3/8 time. Different touches can be used to bring out the three motifs to good effect, varying the voicing for the repeats. It gives the player a chance to relax before the most dangerous of all the toccatas, Variation 20. Here Bach is obviously writing for a performer who is totally fearless and in command of the instrument. It is not just a display of technique, however. The notes are nothing without the joy and humour that are present in abundance, especially when he engages in ‘ batteries’ (a way of breaking chords) in bars 25 to 28. As is typical with Bach, often the most joyous moments are followed by a complete change in mood, and Variation 21 takes us back to the key of G minor with maximum effect. The expressiveness of this canon at the seventh is emphasized by the chromatic descent of the bass which, in the third bar, picks up the swirling opening motif of the canon. It is poignant to be sure (especially with the unexpected and wonderful F natural in the last bar), but should not be unduly slow. True pathos in the minor key is yet to come.

I always get a feeling of rebirth with the onset of Variation 22. The return to G major is partly responsible for this, but so too is the solidity of the four-part writing. Marked ‘alla breve’ and using much imitative dialogue in the style of a motet, it seems to begin a sequence which leads beautifully to the conclusion of the work. For someone who is intimately acquainted with the piece, the end is now in sight and we know where we have to go to get there. Bach really has fun with Variation 23, in which the hands engage in a game of catch-me-if-you-can, displaying various gymnastics along the way. They end up tumbling on top of each other (bars 27 to 30), ending their routine brilliantly together on the last chord! These flurries of double-thirds and sixths are really pushing the limits of keyboard technique as it existed at the time, paving the way for future composers. Again we have this wonderful feeling of joy and delight not just in the music itself but also in its execution. After such antics, the canon at the octave in Variation 24 creates a beautiful sense of repose. It is a pastoral in 9/8 time and the only canon where the leading voice switches between the parts in the middle of a section (bars 9 and 24). The major third in the right hand of the last bar leads perfectly into the minor third in the left hand beginning the next variation. Between these two chords, however, there is a total change of atmosphere.

Variation 25 is, without a doubt, the greatest of all the variations, demanding the utmost in musicianship and expressiveness. Returning to the rhythm of the opening sarabande, Bach writes an arioso of great intensity and painful beauty in which the agonizing chromaticisms show that Romanticism is not far away. Famously called ‘ the black pearl’ by Landowska, its slow tempo (marked Adagio by Bach in his Handexemplar) makes it much longer than any other variation although it has the same number of bars. The ‘repeated note’ ornament at the beginning, which was often used by Bach for a jump of a sixth in impassioned music, is wonderfully expressive and very vocal, and was adopted by Chopin who used it repeatedly. The final descent of the melody ends with a clashing appoggiatura on the tonic, after which the tension is released. As with Bach’ s greatest works in this vein (I think of the sarabande from the Sixth Partita, for instance), we feel that the external world must not intrude on this most private of moments.

The hardest thing to pull off in a complete performance of the ‘Goldberg’ is to gather up the energy and concentration needed for Variation 26 after emptying everything from inside yourself in Variation 25. With only a few seconds’ break, you are thrown into another virtuoso toccata where, for a lot of the time, the arms are crossed over each other. Retaining the sarabande rhythm, but of course much faster, Bach nevertheless writes two time-signatures: 18/16 for the running semiquavers and 3/4 for the accompanying chords, with 18/16 winning out in the end when both hands take off and run in the last five bars. The appoggiaturas on the second beat of the bar (which I add on the repeats) were found in the Handexemplar and are not printed in every edition. They are effective if you feel like adding even more notes! Having successfully negotiated this one, you can feel you’ re now on the home stretch.

The last canon, Variation 27, is at the interval of a ninth and is the only one in which Bach abandons a supporting bass. Staying within the harmonic outline of his theme, the two canonic voices chatter away in a friendly sort of dialogue, slightly tinged with mischief before coming to a very abrupt end. Bach then launches into Variation 28, a study in written-out trills if ever there was one. The continuing sense of joy is characterized by the wide leaps which accompany them and the bell-like notes which mark the beat. A good piano with an easy action and great clarity is necessary to bring this one off satisfactorily. With no let-up allowed, the last of the toccatas, Variation 29, opens with joyous drumbeats in the left hand followed by chords hammered out on the two keyboards (or in this case one). Doubling the octave leaps in the left hand give it the required extra power. I feel it should begin somewhat like a free improvisation, but then be strictly in time for the descending cavalcades of notes that follow. If Beethoven comes to mind in the previous variation, then Liszt is surely not far away in this one! It leads us triumphantly into Variation 30, which we expect to be a canon at the tenth—but Bach always has something up his sleeve. In this case it is a Quodlibet (literally meaning ‘ as you please’ ). A quodlibet was a kind of musical joke in which popular songs, usually of opposing character, were superimposed. This could be done at a family reunion, most likely after a hearty meal and lots of beer and wine. We know that once a year the Bach clan (an enormous one and full of professional musicians) met at such gatherings, beginning their festivities religiously with a chorale, and ending in complete contrast with an improvised quodlibet, the words of which were purposely humorous and often very naughty. For this final variation Bach chose two folksongs, the words of which are:

I’ve not been with you for so long.

Come closer, closer, closer.

and

Cabbage and beets drove me away.

Had my mother cooked some meat then I’d have stayed much longer.

In choosing these folksongs, Bach deftly combines his sublime thoughts with the everyday, and brings us a conclusion full of warmth and joy. For someone who was always a workaholic and to whom discipline came naturally (even in the last days of his life he didn’t let blindness deter him, and dictated his final work to his pupil and son-in-law Altnikol), he also certainly knew how to enjoy life and to share his humanity with us. But now the party is over, the crowd disperses, and the Aria returns, as if from afar. Rather than stating it affirmatively, as it appeared at the beginning, it should appear veiled and even more beautiful in retrospect. Surely this is one of the most moving moments in all of music, and it speaks to us with great simplicity. Our journey has come to an end, yet we are back where we began.

We might well ask ourselves why this work has such an enormous effect on us, as I believe it does. It is certainly one of the most therapeutic pieces of music in that we always feel better for having listened to it.The beauty, joy and fulfillment that Bach shares with us are powerful healers, and give us momentarily the sense of completeness we seek. Perhaps, however, the true reasons should remain a mystery. When writing about the ‘ Goldberg’ , it has become almost traditional, ever since Ralph Kirkpatrick wrote the preface to his excellent edition of the work in 1934, to quote a passage from Sir Thomas Browne’s Religio Medici (1643), and I make no exception here:

There is something in it of Divinity more than the ear discovers. It is an Hieroglyphical and shadowed lesson of the whole World, and creatures of God; such a melody to the ear, as the whole World, well understood, would afford the understanding. In brief it is a sensible fit of that Harmony which intellectually sounds in the ears of God.

From CD Liner notes by Angela Hewitt © 2016

Special thanks to Hyperion Records

Angela Hewitt

Angela Hewitt occupies a unique position among today’s leading pianists. With a wide-ranging repertoire and frequent appearances in recital and with major orchestras throughout Europe, the Americas and Asia, she is also an award-winning recording artist whose performances of Bach have established her as one of the composer’s foremost interpreters. In 2020 she received the City of Leipzig Bach Medal: a huge honour that for the first time in its 17-year history was awarded to a woman.

In September 2016, Hewitt began her ‘Bach Odyssey’, performing the complete keyboard works of Bach in a series of 12 recitals. The cycle was presented in London’s Wigmore Hall, New York’s 92nd Street Y, and in Ottawa, Tokyo and Florence. After her performances of the complete Well-Tempered Clavier at the 2019 Edinburgh Festival, the critic of the London Times wrote, “…the freshness of Hewitt’s playing made it sound as though no one had played this music before.”

Hewitt’s award-winning cycle for Hyperion Records of all the major keyboard works of Bach has been described as “one of the record glories of our age” (The Sunday Times). Her discography also includes albums of Couperin, Rameau, Scarlatti, Mozart, Chopin, Schumann, Liszt, Fauré, Debussy, Chabrier, Ravel, Messiaen and Granados. The final CD in her complete cycle of Beethoven Sonatas (Op.106 and Op.111) will be released in 2022. A regular in the USA Billboard chart, her new album Love Songs hit the top of the specialist classical chart in the UK and stayed there for months after its release. In 2015 she was inducted into Gramophone Magazine’s ‘Hall of Fame’ thanks to her popularity with music lovers around the world.

Conducting from the keyboard, Angela has worked with many of the world’s best chamber orchestras, including those of Salzburg, Zurich, Lucerne, Basel, Stuttgart, Sweden, and the Britten Sinfonia. One recent highlight was her debut in Vienna’s Musikverein, playing and conducting Bach Concertos with the Vienna Tonkünstler Orchestra. In 2021/22 concerto performances include the Royal Stockholm Philharmonic, Helsinki Philharmonic and Toronto Symphony orchestras, Orchestra Ensemble Kanazawa and Concerto Budapest (UK tour), while recitals take place in London, Rome, Leipzig, Dortmund, Tallinn, New York, Philadelphia and Tokyo, among many others. In July 2022 Angela is Chairman of the Jury of the prestigious International Bach Competition Leipzig.

Her frequent masterclasses are hugely appreciated. When all concert activity abruptly stopped in spring 2020 due to the pandemic, Angela went online to share daily offerings of short pieces—many of which form the basis of teaching material. Her fans were thrilled, and she was happy to inspire them and stay in touch.

Born into a musical family, Hewitt began her piano studies aged three, performing in public at four and a year later winning her first scholarship. She studied with Jean-Paul Sévilla at the University of Ottawa, and won the 1985 Toronto International Bach Piano Competition which launched her career. In 2018 Angela received the Governor General’s Lifetime Achievement Award, and in 2015 she received the highest honour from her native country – becoming a Companion of the Order of Canada (which is given to only 165 living Canadians at any one time). In 2006 she was awarded an OBE from Queen Elizabeth II. She is a member of the Royal Society of Canada, has seven honorary doctorates, and is a Visiting Fellow of Peterhouse College in Cambridge. In 2020 Angela was awarded the Wigmore Medal in recognition of her services to music and relationship with the hall over 35 years.

Hewitt lives in London but also has homes in Ottawa and Umbria, Italy where fifteen years ago she founded the Trasimeno Music Festival – a week-long annual event which draws an audience from all over the world.

Ian Alexander

Ian Alexander returned to his roots on the West Coast in 2007, after a 25-year career with the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation in Toronto, where he worked in Radio, Television and Digital Media as an on-air host and programming leader in the classical music area, and later as a senior executive at the corporate level. For six years, he hosted the nightly concert program Arts National on CBC Stereo.

Since leaving the CBC, Ian has worked extensively as a consultant, trainer and facilitator, both in Canada and abroad, specializing in strategic planning, organizational development and communications counsel in the not-for-profit sector. He has worked with numerous arts and culture organizations in Victoria, Vancouver, Toronto and elsewhere.

Ian co-chairs the very active Music Committee of Christ Church Cathedral in Victoria, which recently entered into a new collaboration with EMV. He was the community representative on the search committee for the new Music Director of the Victoria Symphony. He has known Angela Hewitt for over thirty years.