The Fox Cabaret | Map

John Reischman, mandolin; Stephen Stubbs, guitar; Tom Berghan, banjo; Brandon Vance, fiddle; Catherine Webster, vocals; Tekla Cunningham, fiddle

This boundary-crossing programme features early and traditional musicians exploring some of the roots of the United States’ folk and popular music. “Old-time” songs are some of America’s own early music. But where did the tunes played by today’s “old-time” musicians come from? Why are so many baroque players drawn to these traditional folk styles and instruments? What were these instruments that people were playing in the 19th century? Why is Stephen Foster considered the father of American popular music? The mid to late 1800’s America witnessed a surge in publications of “popular” music: Civil War songs, slave songs, cowboy songs, minstrel plays and parlor songs, along with hymns and revival tunes. For a time Foster himself made a living composing minstrel shows, but in later life turned back to his earlier “art song” tradition of parlor music.

An American Tune spans this half-century, tracing particularly the path of old world British Isles folk music to the isolated rural areas of the United States. Catherine Webster (soprano) and Stephen Stubbs (lute, guitar and conductor) have spent careers based on the exploration of 17th and 18th century European music traditions and are now turning their interest to some of the first popular music of their own country. They’ve come together now with other musicians with feet in both the early music and traditional folk world – Brandon Vance, baroque violinist and champion Scottish fiddler, Tom Berghan, historical banjo player, and the brilliant Vancouver-based mandolinist John Reischman to create a gorgeous program of Foster songs, 19th-century hymns and reels, and exquisite arrangements of Appalachian early folk tunes and ballads. Webster and Stubbs find themselves perfectly at home in the sometimes lively, often plaintive and haunting melodies of 19th-century America – Webster’s phrasing and emotional understanding and Stubbs’ utter mastery of any instrument in his hands (this time a beautiful 19th-century parlor guitar) give this program life beyond any classification, all complimented by the string players who take virtuosic turns themselves.

Presented in cooperation with Music on Main. Generously sponsored by Chris Guzy & Mari Csemi.

Programme

Stephen Foster

Hard Times (1854)

Nelly Bly (1849)

Slumber my darling (1862)

Angelina Baker (1850)

Instrumental set

The Braes of Auchtertyre

Billy in the Lowland/Billy in the Lowground

The Banshee

Abraham Lincoln

Old Kentucky Home (Stephen Foster, 1853)

Listen to the Mockingbird (words by Septimus Winner, music Richard Milburn, 1855)

I wish I was in Dixie (Daniel Emmett, 1859)

The Year of Jubilo (Henry C. Work, 1862)

Battle Cry of Freedom (George Frederick Root, 1862)

INTERMISSION

Westward Expansion

Buffalo skinners (trad. after 1873)

Cumberland Gap (mid-19th century folk song)

Come, come, Ye Saints (words by William Clayton 1846 to English folk song All is Well)

Hop Light Ladies

Instrumental set

The Galway

Cuckoo’s Nest

Julie Ann Johnson

The Devil in the Strawstack

Murder Ballads

The Wind and the Rain

Little Sadie

Come all ye fair and tender ladies

Silver Dagger

Programme notes

The subject of American music is so vast that no single program or approach could purport to give even an overview of the subject. To get an idea of this impossibility, just imagine a program that attempted to portray “European music”. And yet, with our classical music culture so heavily reliant on the European tradition, it might be tempting to think of American music as a mere tributary of that mighty river, akin to Scottish or Polish music. The reality however is that the entire complex of European traditions as well as many African ones poured into the American continent and, over the course of centuries, created entirely new hybrid forms.

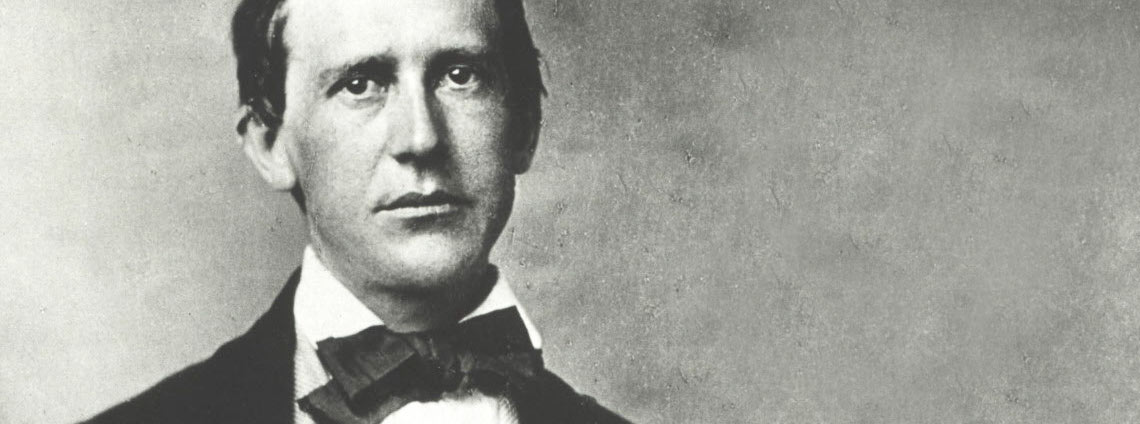

Looking narrowly at the classical mainstream in Europe – the Symphony Orchestra and related chamber music ensembles – it took a considerable time for even the cultural capitals of the Northeast to establish the necessary institutions to continue in this vein, and even then, American composers and instrumentalists often suffered an inferiority complex vis-à-vis their European counterparts. So, to begin an exploration of American music in the 19th century, rather than taking the orchestra, or any other fixed ensemble, as the point of departure, we looked at the figure of Stephen Foster, arguably the “father of American song”. Stephen Foster’s personal ancestry (Irish and English) as well as his possible study with a German-born musician, Henry Kleber, may both have played a role in the kind of composer and musician he became. Certainly he had a native gift for melody, and the memorable lilt of his best tunes shares something essential with Scottish and Irish folk songs that had been the mainstay of British parlor music since the 18th century. This was one side of his large body of song: parlor songs “of the hearth and home”, cultivated by anyone with a piano or guitar with which to accompany the voice. The other side of his production was aimed at the professional troupes that called themselves “minstrel shows”. He signed a contract with E.P. Christy of “Christy’s Minstrels” giving Christy exclusive first-performance rights to every new song he wrote. There is no adequate way in a short essay to grapple with the unsettling phenomenon of black-face minstrelsy in the history of American music, but it was also too pervasive to ignore. To take only the positive side into account, it was a vehicle for the influence of African music, dance and instruments (particularly the banjo) to put down widespread and permanent roots in our musical culture. Our first set of Foster songs alternates the ‘home and hearth’ side of his output in songs like Slumber my Darling, with the minstrel-show songs Nelly Bly and Angelina Baker. That Foster himself wished to place himself in the context of the European classical tradition can be seen most clearly in his publication in 1854 of The Social Orchestra, in which he wove some of his most popular songs (like Old Folks at Home) into chamber music fantasies which he called ‘Quadrilles’, and placed these alongside “Gems from Lucia” – arrangements for various instruments of highlight’s from Donizetti’s Lucia di Lammermoor! Foster’s own life extends into the period of the Civil War, and he even wrote a few Civil War songs in support of the Northern unionist side (We are coming, Father Abraham from 1862), but we decided to venture into that era by following the most iconic figure of the age: Abraham Lincoln.

Lincoln was very fond of music and once told his friend Henry Clay Whitney “all other pleasures have a utility, but music is simply a pleasure and nothing more, and I fancy that the creator, after providing all the mechanism for carrying on the world, made music as a simple unalloyed pleasure.” Stephen Foster’s song My Old Kentucky Home from 1852 must have struck a sentimental resonance in Lincoln for his early days in a log cabin in rural Kentucky, just as his fondness for Listen to the Mocking Bird likely held a personal meaning. Of the latter he once said “it is as sincere as the laughter of a little girl at play”, but dealing as it does with the melancholy of lost love, it may have connected to the loss of his first love, Ann Rutledge, to typhoid at the age of 22. The iconic song of the Civil War era South, I wish I was in Dixie, was ironically composed by the Northerner Daniel Emmett in 1859 for his own minstrel show. Nevertheless, it became the unofficial anthem of the Confederate States. Lincoln, on hearing of the Confederate surrender at Appomattox, asked the military band to play Dixie, and it remained one of his favorite songs. He later said “that tune is now Federal property and it is good to show the rebels that, with us in power, they will be free to hear it again.” The Year of Jubilo, another minstrel-show song, is a vision of the celebration of freed slaves whose master has been frightened away from the plantation by the approach of Union forces. The Battle Cry of Freedom written in 1862, a patriotic song for the Union cause, became one of the most popular songs of the era, and the distinguished American pianist and composer Louis Moreau Gottshalk wrote that “it should be our national anthem”. Besides the Civil War, the other most prominent feature of 19th century America was westward expansion. This phenomenon also inspired a body of music. Cumberland Gap, a narrow pass in the Appalachians near the junction of Tennessee, Kentucky and Virginia, became symbolic of the hardships of the journey, and also gave its name to one of the most popular folk songs of the latter 19th and early 20th centuries. The Buffalo Skinners is a folk song that recounts the 1873 buffalo hunt on the southern plains. It was collected in 1918 by John Lomax for his Cowboy songs, and Other Frontier Ballads, and popularized by Woodie Guthrie in his recording of 1945. Come, come ye saints is such a well-known hymn within the Mormon tradition that it serves as an icon of identity for that community, featuring prominently in celebrations of Pioneer Day in Utah. The lyrics were written in 1846 by the Mormon poet William Clayton, but the music is the popular English folk tune All is Well. Playing the four part setting on violins and guitar with the banjo taking an ornamental approach to the melody provided us with one of the true “aha” moments of our work on this program. The connection to the early 17th century sound of the English “broken consort” was immediate and unmistakable. In the earlier context, plucked and bowed strings provide the harmonic framework while the solo lute decorates the melody – this is the earliest form of specifically orchestrated music in the European tradition, and here it is again in a hymn from Utah! All of the instrumental pieces on our program are derived from the tradition of American folk fiddling, which in turn has its roots largely in Celtic traditions from Ireland and Scotland.The relative cultural isolation of Appalachia in particular allowed for the preservation of those traditions, often beyond the time of their life- span in the countries of origin– much as Elizabethan English speech patterns with “Thee and thou” persisted there into our own time. Finally, we were attracted to a special repertoire of American folk-song with a macabre theme: the murder ballad. Murder ballads have been a notable proportion of ballads going back at least to their collection and publication in broadsheets in 17th century Europe. American murder ballads are often re-workings of those European ballads. Folk song is always balanced between preservation and innovation. An important figure for the preservation of English folk song in particular was Cecil Sharp (1859-1924). Besides his important activity collecting songs in many parts of England, he also came to the states from 1916-1918. His field work in remote regions of southern Appalachia has given us the basis of English folk art, often preserved there in an earlier form than what was known in contemporary England. The transformation of the timeless beauty of Come all ye fair and tender ladies into the driving rhythms of Silver Dagger in its more modern bluegrass guise can attest to the durability of folk song in the face of musical evolution.

Stephen Stubbs, 2015

John Reischman, mandolin

John Reischman is one of the premier mandolinists of his generation. He’s a master instrumentalist capable of swinging between re-inventions of traditional old-time tunes, deconstructions from the bluegrass repertoire, and compelling original tunes, many of which have become standards. He’s also a powerful bandleader, touring his band the Jaybirds all over Canada and the United States. But most of all, he’s an understated visionary, the kind of master craftsman whose music is virtuosic without ever being flashy and who is renowned for his impeccable taste and tone as an artist. John Reischman embodies the true spirit of acoustic music in the 21st century.

He’s a master instrumentalist capable of swinging between re-inventions of traditional old-time tunes, deconstructions from the bluegrass repertoire, and compelling original tunes, many of which have become standards.A Juno-nominated and Grammy-award winning artist, John Reischman is known today for his work with his band the Jaybirds and his acclaimed solo albums, but he got his start as an original member of the Tony Rice Unit in the late 1970s. With the Tony Rice Unit, Reischman helped define the “new acoustic music” movement in bluegrass thanks to their high profile albums on Rounder Records. Building this sound, Reischman was of course influenced early on by Monroe’s mandolin playing, but also by the playing of early bluegrass mandolinists like Sam Bush, David Grisman, and jazz mandolinist Jethro Burns. Living in the Bay Area in the 80s, Reischman toured and performed with seminal bluegrass band The Good Ol’ Persons, cementing his reputation as a powerful mandolinist with an original vision for the instrument. He moved to Vancouver, British Columbia in the 1990s and formed The Jaybirds, but Reischman never stopped his musical explorations. In 1996, he won a Grammy as part of Todd Phillips’ all-star tribute album to Bill Monroe. Over the years, he’s overseen collaborations with a remarkably wide range of artists, like bluegrass singer Kathy Kallick, to guitarist Scott Nygaard, banjo wiz Tony Furtado, Chinese Music ensemble Red Chamber, Brazilian multi-instrumentalist Celso Machado, singer songwriter Susan Crowe, and more.

Stephen Stubbs, guitar

Stephen Stubbs, who won the GRAMMY® Award as conductor for Best Opera Recording 2015, spent a 30-year career in Europe. He returned to his native Seattle in 2006 as one of the world’s most respected lutenists, conductors, and baroque opera specialists.

In 2007 Stephen established his new production company, Pacific MusicWorks, based in Seattle. He is the Boston Early Music Festival’s permanent artistic co-director, recordings of which were nominated for five GRAMMY awards. Also in 2015 BEMF recordings won two Echo Klassik awards and the Diapason d’Or de l’Année.

In addition to his ongoing commitments to PMW and BEMF, other recent appearances have included Handel’s Amadigi for Opera UCLA, Mozart’s Magic Flute and Cosi fan Tutte in Hawaii, Handel’s Agrippina and Semele for Opera Omaha, Cavalli’s Calisto and Rameau’s Hippolyte et Aricie for Juilliard and Mozart’s Il re pastore for the Merola program in San Francisco. He has conducted Handel’s Messiah with the Seattle, Edmonton, Birmingham and Houston Symphony orchestras.

His extensive discography as conductor and solo lutenist includes well over 100 CDs, which can be viewed at stephenstubbs.com, many of which have received international acclaim and awards.

Stephen is represented by Schwalbe and Partners (schwalbeandpartners.com).

Tom Berghan, banjo

Tom Berghan was transported into the old-time banjo scene, a couple years ago, as a refugee from the Early Music camp, rockabilly bands and various other genres he’s delved into throughout a rich lifetime of musical exploration and achievement.

Even a casual participant in the premier Internet banjo community – banjohangout.com – couldn’t possibly have missed Tom’s arrival into the world of all things banjo.

It was immediately obvious that his profound musical expertise was catapulting him towards unusual and gorgeous renditions of early American music. It’s been fascinating to see Tom’s evolution as a wonderful banjoist through his musical uploads to banjohangout.com. On the hangout, banjoists representing a wide range of styles appreciate Tom’s musical offerings and enjoy the creative musical renditions he comes up with, on his seemingly ever-expanding collection of interesting banjos.

Besides Tom’s extraordinary level of musicianship, his personality and dedication really come through his prolific contributions to banjohangout.com where he can often be found hanging out – communicating from high level of erudition and with a great sense of humor. This is a guy on a musical mission; we can look forward to lots of superlative banjo music from him.

Shortly before I first found out about Tom, I had written a piece about Adam Hurt’s musical finesse, saying it was as if a lutenist had picked up a banjo. Then I met Tom – a lutenist who had picked up a banjo. In fact, Tom had specialized in music of the 17th century and had been among the central figures of the American Pacific Northwest early music scene – founding and directing an organization devoted to the study and performance of historical dance and dance music from the Renaissance and Baroque periods.

And that’s just one part of Tom’s résumé.

Through his ability to turn any instrument into an incredibly expressive voice, and through his creative use of various types of banjos, Tom Berghan clearly stands poised, ready to make a lasting and meaningful contribution to the world of banjo music.

Brandon Vance, fiddle

Internationally acclaimed Scottish fiddler and violinist, Brandon Vance, is the recipient of Scotland’s 2017 Royal National Mòd “Sutherland Cup” in Scottish Fiddle, as well as being the youngest to win the U.S. National Open Scottish Fiddling Championship in both 1999 and 2001.

Vance has performed and taught internationally, serving as a guest lecturer at the University of Limerick’s Irish World Academy, appearing as guest artist for the 50th Anniversary of the Armagh Piper’s Club at the William Kennedy Piping Festival, and being selected as a featured soloist at the 2017 Scottish Royal National Mòd in Fort William. With a M.M. from the Cleveland Institute of Music, one of the continent’s most distinguished conservatories, Vance performs with Seattle-based Pacific Music Works, Early Music Vancouver, Northwest Sinfonietta, mandolinist John Reischman, vocalist Nadia Tarnawsky, Alex Fedoriouk, uilleann piper Eliot Grasso, and composer Stephen Rice. In addition to being a founding member of Celtic Ensemble Dréos and World Music Ensemble Alchymeia, Vance is a composer with a distinctive melodic and harmonic vocabulary, having given the world premiere of his original composition “Gael Storm” for fiddle and orchestra with the Cleveland Pops Orchestra at Severance Hall. Vance has had the honor of serving as music director and violin soloist for the world premiere of “Odyssey of These Days,” a work composed by Eliot Grasso, and presented at the Hult Center in Eugene, Oregon,as a musical response to a set of nine paintings by Wesley Hurd that deal with loss, grief, and hope. Recently, Vance has worked with his Celtic ensemble Dréos to compose, arrange, and perform music for the world premiere of Ballet Fantastique’s “Sleepy Hollow”. In addition to having a well-established international career as a violinist and fiddler, Vance is also emerging as a traditional Gaelic singer, having been ranked 3rd in the Skye and Sutherland Open Competition at the 2017 Royal National Mòd.

Catherine Webster, vocals

Soprano Catherine Webster is engaged regularly by many leading early music and chamber ensembles in North America. She has appeared as a soloist with Tafelmusik, Tragicomedia, Theatre of Voices, Netherlands Bach Society, Apollo’s Fire, American Baroque Orchestra, Magnificat, Musica Angelica, El Mundo, Four Nations Ensemble, Studio de Musique Ancienne de Montreal, Ensemble Masques, Les Voix Baroques, Early Music Vancouver, and at the Vancouver, Berkeley, Montreal and Boston Early Music Festivals.

Active also in contemporary music, Webster has appeared with The Kronos Quartet in Terry Riley’s Sun Rings and with Theatre of Voices and the Los Angeles Philharmonic in John Adam’s Grand Pianola Music.

Catherine Webster is a frequent collaborator with baroque opera directors Stephen Stubbs and Paul O’Dette, appearing under their direction in Early Music Vancouver’s production for the 2013 edition of Festival Vancouver in Monteverdi’s L’Incoronazione di Poppea and the premiere of Mattheson’s Boris Goudenov for the Boston Early Music Festival. She has recorded for Harmonia Mundi, Naxos, Musica Omnia, Analekta and Atma.

Catherine holds a Master’s in Music from the Early Music Institute at Indiana University and has been a guest faculty member and artist for The San Francisco Early Music Society’s summer workshops and the Madison Early Music Festival.

Tekla Cunningham, fiddle

Praised as “a consummate musician whose flowing solos and musical gestures are a joy to watch”, and whose performances have been described as “ravishingly beautiful”, “stellar”, “inspired and inspiring”, violinist Tekla Cunningham enjoys a multi-faceted career as a chamber musician, concertmaster, soloist and educator devoted to music of the baroque, classical and romantic eras. She is concertmaster and orchestra director of Pacific MusicWorks, and is an artist-in-residence at the University of Washington. She founded and directs the Whidbey Island Music Festival, now entering its fourteenth season, producing and presenting vibrant period-instrument performances of music from the 17th through 19th centuries, and plays regularly as concertmaster and principal player with the American Bach Soloists in California.

Tekla’s first solo album of Stylus Phantasticus repertoire from Italy and Austria will be released next year – music by Farina, Fonatana, Uccellini to Biber, Schmelzer and Albertini, with an extravagant continuo team of Stephen Stubbs, Maxine Eilander, Williams Skeen, Henry Lebedinsky.

Tekla received her undergraduate degree in History and German Literature at Johns Hopkins University while attending Peabody Conservatory. She studied at the Hochschule für Musik und Darstellende Kunst in Vienna Austria with Josef Sivo and Ortwin Ottmaier, and earned a Master’s Degree in violin performance at the San Francisco Conservatory with Ian Swenson.